- Home

- Theodora Armstrong

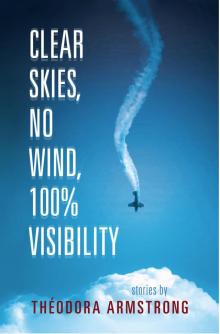

Clear Skies, No Wind, 100% Visibility Page 8

Clear Skies, No Wind, 100% Visibility Read online

Page 8

“Tell me what you think,” Martin says, as he pours a taster for Topher as well. Topher sips the wine and swishes it around before swallowing and making some light smacking sounds on the roof of his mouth. He comes to Marinacove in the afternoon between lunch and dinner service on a regular basis to drink and to poach the wait staff. He doesn’t believe in drinking in his own establishment. Charlie doesn’t care about that kind of thing. The result is the same: they are both well on their way to being sloshed in time for the dinner rush. “Acidic,” Topher pronounces. “Notes of blackcurrant and raspberry.”

“Tastes like toilet water,” Charlie says, slurping up the last dregs of wine and pushing his glass back at Martin. There’s suddenly a lightness in his brain: the thick, stagnant chaos that filled his head this morning is dissipating with the tickle of alcohol.

“How about this one?” Martin joins them in the tasting.

They work their way through most of the wines on the list, even the ones they’ve carried for years, until the charade runs its course and Martin finally cuts to the chase and pours Charlie a long Crown and Coke. Charlie counts the pour — one, two, three, four — giving Martin a grim but approving nod. It’s rude to refuse a drink from a friend and Martin is his good friend. He notices Martin already has his own hidden below the bar in the well. He sets Charlie’s drink on the counter with a clink and a tinkle that makes Charlie smile. “For courage,” Martin says.

“I don’t need it,” Charlie says. “But I’ll drink anyway.”

“He’s asking for a raise today,” Martin explains to Topher.

Charlie shakes the ice cubes in his glass feeling annoyed. “You’re bleeding.” Charlie motions to Martin’s lip. “Right here.”

Martin grabs a bar napkin and dabs at the cut.

“I’ll join you in that drink, then,” Topher says. There’s a twinkle in his eye Charlie doesn’t appreciate. Martin pours another Crown and the three men cheers awkwardly, an unexpected air of camaraderie — a brief entente among alcoholics. “How’s your mother?” Topher asks, giving his drink a gentle stir with his swizzle stick. Many years after his father died, his mother went into the care centre, and for years Topher was the only person other than Charlie who ever dropped in to see her. He suspects there may have been something going on between them, probably long before his father’s death. He wonders how much Topher knows, if his mother ever confided in him or spoke of the late-night cooking sessions at home, his father spinning like a whirling dervish in nothing but boxers, his clothing in a pile in the hallway, piping sausages hopping out of the skillet, skidding across the floor as his father chased after them with a fork, shouting, Watch out! Maudit! Plates were smashed; a bottle of olive oil shattered into a million bright gold pieces across the floor; the blood-red brilliance from a smashed glass of wine looked like evidence from a crime scene. His bleary-eyed mother would stumble out of the bedroom, but the only thing she ever said was don’t forget to turn off the stove. She lived in constant fear of his father burning down the house, but she never told him to go to bed or to quit drinking.

Even though her mind is fading, his mother still talks about that one time Topher brought flowers to the care centre — white begonias. It’s as though she’s forgotten that Topher had vied constantly for Charlie’s father’s job, waiting for the opportunity that eventually presented itself.

“So they can afford to hand out raises here?” Topher says, glancing around the empty restaurant. Outside the clouds have darkened and the ocean is threatening the seawall, menacing the last few hardcore joggers on their afternoon runs.

“Who eats in the middle of the afternoon?” Charlie wants the words to sound tart, but instead they get lost in a yawn and end up sounding lazy.

“Ah.” Topher smirks and takes a sip of his drink. “I’m just giving you a hard time, Charlie.” He runs his finger through a patch of dust on the bar. “What were your numbers like this week?” Charlie shrugs and takes a gulp. He’d rather concentrate on finding the bottom of his glass as quickly as possible than acknowledge Topher’s smug smile. “We did fifty,” Topher says. “Not our best, but better than last year.” He leans back and rubs his belly as if it were a piggy bank. Martin whisks away his empty glass and replaces it without exchanging a word, a fresh napkin placed under the drink. They did less than half that number last week.

“We’re doing fine,” Charlie says. He fudged the books to make up for twenty pounds of lobster for a seafood risotto that never sold. Actually, he has massaged the numbers several times over the past few months, something that becomes easier the more often you do it. Charlie jiggles the ice in his glass, hoping Martin will get the message and replenish his drink too.

“I don’t know. I’ve been making fuck all,” Martin says, picking at the congealed blood sealing his cut.

“November is a quiet month,” Charlie says, jiggling his glass harder, sending ice across the bar floor. Martin misses his signal. “We’re going to be booked solid for the holidays.”

“Really?” Martin does a poor job of hiding his surprise. He walks over to the hostess stand and flips through weeks in the reservation book.

“They’re not all in there yet,” Charlie calls to him. “I haven’t had time to enter all the big parties.” He has one Post-it note in the back with Williams, party of seven, Dec 12th scrawled on it.

“Sure, you’ll be busy, man of your talents. Your father would be proud,” Topher says. The comment is insincere. An acrid smell is wafting from the open kitchen. From the bar, Charlie can see Rich, James, and Tara working at their individual stations.

“Do you smell something burning?” Topher says.

Charlie pours the drink himself. “Still bleeding,” he says to Martin, pointing at his lip, before turning to make his way to the kitchen. Outside the waves have overtaken the seawall and the joggers have all gone home.

To Topher, Charlie’s father was the pinnacle of success. But Topher never saw the man on the couch at four in the morning, bathed in the blue glow from infomercials on the boob tube, stuffing his fat son. It was at that late hour that Charlie learned the art of eating — how to hold his knife with the handle in his palm, and his fork with the tines pointed downward; how to tip his bowl and take the soup from the side of the spoon, how to tear his bun into bite-sized pieces before bringing it to his lips, how to pour first for his father then for himself. Charlie would lie in bed afterward, wide awake, rubbing his near-bursting belly. He’d listen to his father snoring on the couch, and as he watched the night sky turn cerulean he’d savour the flavours still lingering on his tongue.

After years of this ritual, Charlie’s teeth turned to chalk; the acid from his midnight meals ate away at the enamel until there was nothing left to protect them. His teeth became soft and useless. It cost his parents a small fortune to repair them.

IN THE KITCHEN, CHARLIE assesses the chaos he knew he would find. People think kitchens are clean places. Their food arrives, the presentation is beautiful, the flavours harmonizing like a barbershop quartet. But no one considers the mess — the anger, the sweat, the bedlam, the burns and cuts and stings it takes to achieve the perfection of those delicate slices of rose-shaped cucumber balanced on the edge of their plate. James is standing at the cold line, his back to Charlie, julienning vegetables, a hand through the flop of bangs across his forehead every ten seconds. A carrot top falls to the floor and he gives it a gentle nudge under the counter. People don’t think about what’s hiding in the cracks of the linoleum. They don’t think about the stinking mop that wipes the floors every night and smells like death. Charlie crosses his arms and waits for someone to notice him standing there. The smoke filling the kitchen offends his nose. Rich is bent over the stove stirring a pot of demi-glace, bouncing to the faint beats floating from the ghetto blaster in the dish pit, the frosted tips of his spiky hair dangerously close to the salamander. On the memo board in the back hall there

’s a picture of him from New Year’s, bare-chested, head thrown back, chugging from a bottle of cheap champagne with his hands tied behind his back. His ability to metabolize alcohol is legendary. Charlie has witnessed the mythos on several occasions. Rich’s expression in the photo can only be described as one of pure delight. In fact, exuberance seems to be Rich’s natural condition.

“I feel like shit,” Tara says, hunched over her rolling pin, a tray of cheese crisps in front of her, ready for the oven. “Fucking Finlandia. I don’t want to be here. I would rather be anywhere than here. I would rather be dead than here.” People don’t think about the hungover baker with nicotine-stained fingers setting those dainty mint leaves on their dessert. People believe when they pay good money for their food, it is made with passion and love. Love!

Charlie throws open the oven door, revealing a tray of blackened parmesan crisps. “These done?” Charlie barks. Tara jumps, noticing him for the first time, and yanks the tray out of the oven.

“Shit,” she says, throwing the tray on the counter with a clatter.

“They’re supposed to look like this,” Charlie says, pulling one of the paper-thin parmesan crisps out of an insert. It looks like dead skin and trembles between his fingers. “They should be done by now. You should be making salad dressing.”

“I was busy this morning.” She’s scraping the burnt crisps into the garbage.

“But why aren’t they done?” Charlie expects to feel agitated, but the alcohol has roused a pleasant hum in his body. It’s making him sleepy — he has to work to maintain his level of anger.

“They take time.” Tara was banging the tray against the garbage can to free the worst victims.

“No they don’t. They’re easy. You roll them out.” Charlie wields the rolling pin, pounding the cheese into the tray. “Throw them in the oven and they’re done. Easy.” Topher is leaning sideways in his seat to get a better look at what’s going on in the kitchen.

“Yes, Chef,” she says. He can see the mental flow of obscenities behind her eyes and this gives him a feeling of satisfaction. “Speed it up.” He tries to snap his fingers, but they feel thick and doughy. “Rich, how’s your mise-en-place?” Rich looks up at him, a wide grin revealing his tiny Chiclet teeth. Charlie is fairly sure he’s stoned. “How you’s, Chef?” Rich uses a knuckle to test a chicken breast sizzling in a pan. Charlie walks over to the cold line, where James is still chopping, and picks up the stock bucket. “Why the fuck is this empty?” James and Tara stare blankly while Rich sings a little ditty and caresses his demi with a spatula. “Look at this,” Charlie says, reaching into the garbage and pulling out potato ends and celery stalks, chucking them on the floor, “Perfectly good, perfectly good.” His shouts ring pleasingly inside his head as he holds up each rejected vegetable part as though it were solid gold. “Money in my garbage,” Charlie grumbles, lowering his voice so it won’t reach Topher’s ears. Charlie digs deeper through the trash can. There’s a crudeness to kitchens that’s never bothered him but would bother anyone else. Rotting garbage doesn’t bother him. Mould doesn’t bother him. Soured dairy doesn’t bother him. He’ll take a solid whiff of any of those things without hesitation. Sometimes he feels the world’s no better off now than it was during the Middle Ages, when everyone threw their piss and shit into the streets. To him, some days, it feels no different. “What the — ” Charlie pulls out a handful of burnt pancetta from the garbage can. The numbers will have to be cooked again this week. “Can someone tell me why there’s twenty dollars’ worth of burnt pancetta crisps in here? Rich?”

“Yo,” Rich says, looking up and grinning like a fool. “You look good, Big Chef.” Charlie has always assumed Rich was misusing the word big, meaning instead great or powerful or almighty, but lately he’s not so sure. He has a feeling Rich may be calling him fat.

“Jesus Christ.” Charlie rubs away the sheen of sweat that’s suddenly sprouted across his brow and sets himself up at his station, leaning into the counter and letting it support most of his body weight. “We have an hour to be ready for dinner service, got that?” He blinks heavily. The pleasurable buzz has turned into a heaviness of the head. He needs another drink. Then he remembers he has one waiting right in front of him. He takes a gulp.

“I think it was one of the day people who burned the pancetta,” Tara says, crouched down at the stove, watching her parmesan wafers. Charlie flaps a hand at her, meaning shut up, pretty please, and begins prepping the chicken breasts, scraping the cartilage off the bone with his paring knife. He finds the work satisfying after dealing with all this incompetence.

An elderly woman wobbles into the empty restaurant in a bright red rain slicker with matching hat and gazes around, glassy-eyed. She turns to make sure Charlie notices her, raising a hand in acknowledgment as high as it will go — about mid-waist — before hobbling to a dirty table Rose still hasn’t cleaned because she’s too busy smoking or ridiculing or doing whatever takes her so goddamn long. The old woman sits down and begins to gently move the plates of congealed food away from her. While Charlie wraps the chicken in thin slices of pancetta, he watches her pick a crumpled napkin up off the table, using it to sweep the crumbs to the floor and then blow her nose. A shiver runs down his spine and bile sloshes around his stomach. He takes a large swig of his drink, diluting the acid threatening his gut. Charlie hates to watch people eat alone. Food is meant to be shared, joined by atmosphere and conversation and good drink. Food is more than sustenance. Food is more than necessity. To him eating a beautiful meal alone is akin to buying your own birthday cake and blowing out candles you lit yourself in your own lonely living room. What’s the point? There are other things that get to him: someone walking alone down the street, indulging in an ice cream cone; or the lonely crinkle of an unwrapped chocolate bar at the bus stop. Anything processed with cheesy strings that hang from the lips makes him shudder. People are careless when they eat alone, more carnal, animal-like. They are more likely to smack their lips, pick their teeth, dribble down their chins, stuff their cheeks, chew with their mouths open. He once broke up with a girl after watching her eat a giant fajita alone at her kitchen table, stuffing in the last bite using each and every finger of both hands to tuck all the corners into her mouth. And he once retched when he came upon the sight of Martin crouched in the back on an overturned bucket a few feet from the dish pit, which was stacked to the ceiling with dirty dishes, shovelling his staff-discounted food down his yap because he had only five miserable minutes between clearing the appetizers off one table and bringing out the entrees to another. Why bother? To Charlie it was unconscionable behaviour. After vomiting into the garbage can, Charlie had tried to kick the bucket out from underneath Martin, but he managed to leap away, saving his dish just in time. “I was hungry,” he explained. He was hungry! For a few weeks there was a ban on staff eating anywhere in Charlie’s sightlines, but eventually Susan vetoed the rule, saying it was unreasonable and potentially in violation of labour laws.

What really gets him, though, are these old ladies. They come for their dinner alone around four o’clock, when no one is around to greet them at the door because all the staff have loped off to eat in the back or smoke in the alley. The ladies either seat themselves or they come over to him and peer up over the pass-bar, always saying something he can’t hear. They all order the same three things on the menu: the crab cakes or the clam chowder or the shrimp salad sandwich. They sit at a window with a view. He can’t watch them gaze at the ocean and then absent-mindedly turn back to their food, select another bite, chew, gaze, chew, gaze. They demand a senior’s discount and pull out their bags of loose change. Rose is always nice to them, stooping to chat, bringing them free coffee, never letting their magenta-lipstick-marked cups find their bottom. There’s always a neat row of dimes, nickels, and pennies left for a tip that clang around in Rose’s apron the rest of the night.

The ladies remind him of his mother. A sharp tickle of bi

le rises in his throat again. He makes sure to never visit the care centre at mealtime, but there are always remnants: lunch carts of half-eaten gelatinous tapioca, smells (culinary and bodily) lingering in the hallways, splatters across Maman’s shirt. He finds it hard to go often. When his father was ill and in the hospital his mother would go dutifully every day to visit him for exactly forty-five minutes, not a minute more. It was only after his father’s death that his mother started complaining about the drinking, about the long hours he worked, complaining about the fact that she never had a holiday, about the things he broke in the house. Only after his death did she start missing the china bowl from her mother and the ceramic dog with the wet-looking eyes that her godmother had given to her on the day of her birth. A month after his father’s death, she took a week-long vacation in Havana. Those were the pictures she had on the wall beside her bed in the care centre. Not pictures of her husband or son, but pictures of her sipping a Cuba Libra in the shade of an umbrella.

The last time he was at the care centre, he decided to mention the baby. She seemed lucid enough to give it a try. He set a takeout container in front of her and planted a plastic fork in the middle of the dish, waiting for the aromas of basil and cream to reach her nose before he told her the news. She fumbled for the fork and ate hurriedly like a person starved. He waited patiently, letting her enjoy the food in peace. The nurses had mentioned that she no longer ate her meals. They’d been giving her supplement shakes a shade of pink that reminded him of Pepto-Bismol or death. He pushed the takeout container closer to her. “C’est bon, Maman?”

Clear Skies, No Wind, 100% Visibility

Clear Skies, No Wind, 100% Visibility