- Home

- Theodora Armstrong

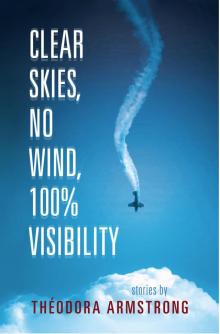

Clear Skies, No Wind, 100% Visibility Page 7

Clear Skies, No Wind, 100% Visibility Read online

Page 7

After his release from service at Le Remoulade, there was a brief stint of house painting, which inadvertently led to real painting and an unexpected epiphany: Charlie was an artist. He gave up cooking, charged a small fortune on his credit card for supplies, and spent his days covered in assorted colours of cracked and flaking paint, body painting large swaths of unstretched canvas spread across the floor, strutting around the house naked, drinking his whiskey-spiked morning (afternoon) coffee, and squishing his cigarette butts (and butt cheeks) onto the canvas. It was only after his father’s death that he got hungry and went back to food. Besides, the paint dried out his skin and a friend informed him that the cigarettes squashed into canvas had been done over fifty years earlier. He worked at a Brazilian barbeque where they carried meat around the dining room on long spears, a Japanese-Italian fusion restaurant where an octopus alfredo was the most popular dish, and a bubble tea café — during his darkest days — where he spent his shifts scratching the itch inflicted by his paper hat and attempting to solve the mystery of the boba bubbles. And then he finally landed his position as head chef at Marinacove.

An extra lane opens on the bridge and the traffic breaks up. The Civic goes shooting through the causeway, evergreens on either side blurring into a long green tunnel. Charlie moves into the middle lane down the Lions Gate Bridge, taking in the West Vancouver mountains and the mansions creeping up the slopes. At the base of all that luxury, a short drive down the hill from the Trans-Canada Highway, across the train tracks and past the main thoroughfare on a quiet street overlooking the ocean and the bridge, is Charlie Beaulieu’s restaurant. During the summer months swarms of sunburned bathers from the beach spill over onto its patio, but once the deck umbrellas are stacked in the corner and the chairs are tilted against the tables to prevent pooled rainwater from rotting the wood, the stream of diners quickly dries up and the only customers left are the regular patrons: the elderly, ruled by habit or limited mobility, and the wealthy, too nervous to cross the bridge and leave their little hamlet of multi-million-dollar homes.

Today he will sit down with Susan to negotiate a salary increase, because Charlie feels he deserves more. He knows food and he loves food and he’s a big man because of it — not morbidly obese or anything, but a bit of a fatso. When Charlie came to the restaurant three years ago, the menu was all over the place — eggrolls alongside pierogi, an Indonesian stir-fry next to a pasta bolognese. The previous chef had been fired after he went across the street for a midnight dip in the ocean with some of the underage staff members and then left his wet underpants to dry in the back hall. Charlie’s fairly sure he’s looking pretty good by comparison. A few days ago he organized an early-morning tasting for the staff. He stood in the middle of the dining room and recited the menu changes as though he were reciting a love poem, everyone squinting at him from under baseball caps and hoodies. The room smelled strongly of a night club — booze and body odour and smoke — until he brought out his food and then the room filled with the aromas of bouillabaisse, salmon terrine, quiche lorraine, and filet mignon. He recited the ingredients and preparation of each dish to the frantic clatter of cutlery. It was like watching a pack of hungover hyenas — save Rose, who ate nothing, and Susan, who sat in the middle of all the chaos eating like she was completing a business transaction, neat mouthfuls chewed precisely. After each robotic machination she would make a note next to the item on the menu. What could she have been writing? Bouillabaisse: sublime. Risotto: transcendent. Duck confit: orgasmic. How could one describe such pleasure with words?

He’s been composing different speeches all week, fine-tuning his approach, but the birthday card has unhinged something inside his brain, caused a short-circuit that has eaten a smouldering hole through his grey matter, and now everything is tumbling out of its compartments, collecting in a big messy pile inside his head. The idea of sorting through the disarray is making Charlie feel unbelievably tired, and he is tired most days; tired of ungratefulness and gluten allergies and Atkins regimes. Charlie’s fatigue is profound and feels like old deep-fryer oil pumping through his arteries. When he pulled out of his underground parking spot this afternoon and drove by the liquor store at Davie and Thurlow, he felt the pull of a super-magnet, the same super-magnet that pulls the escaped IV-wheeling alcoholics from the hospital down the street to the liquor store’s front door in search of cheap whiskey. Some days he feels no different than those parched men hobbling along the sidewalk, clutching the back of their hospital gowns to keep their bare asses from hanging out.

The Civic zips down the alley, thumping over the speed bumps, and pulls into the small parking lot behind Charlie’s restaurant. Back here there is no hiding the truth. Seagulls dive-bomb the garbage bins and scatter the remnants of last night’s dinner service all over the lot. The paint is peeling and a faded sign from days gone by advertises Cheap Gyoza Tuesdays. A broken grease trap leaks a rank odour akin to death. There’s always a cluster of angry and bedraggled waitstaff smoking on his back steps. It isn’t a sight that promotes the appetite. Any tiny morsel of hope Charlie may have mustered while driving to his restaurant is always shattered when he pulls into his parking spot. They irritate him, the squawking seagulls and the squawking waitstaff. Ack, ack — scavengers, all of them.

Of course, technically Marinacove is not Charlie’s restaurant. It’s owned by a group of has-been sports stars with shares in three different establishments in the Lower Mainland. Mostly they remain anonymous, but once a year the Logan Group calls a meeting to discuss something pointless like bringing pierogi back onto the menu. He dreads those meetings — those square-shouldered thick-necks coming in to tell him how to run the restaurant. If he were in charge of the place it would never have become this cesspool of miscreants and deadbeats wallowing in their own puddles of worthlessness.

Charlie lugs his tired body up the back steps of the restaurant, the loitering of unkempt staff parting for him as choruses of hey, Chef bubble around him. He grumbles as he elbows his way through — his usual shtick — and they all grin good-naturedly (save Rose) like he’s some sort of cartoon character put on this Earth for their entertainment. He’s already picked out a staff member to yell at tonight: the teenage dishwasher sitting at the bottom of the steps, looking pale and waterlogged, as though he’s just been pulled from the ocean.

Charlie pulls his toque down over his ears. A gust of wind blows in off the water, the cold biting at his earlobes. He’s more exposed to the elements with his bald head, more vulnerable to illness.

“Chef, guess what I found in my pocket this morning?” Martin, the bartender, says, rooting around in his brown leather jacket. You can never tell Martin is drunk until, at 3 a.m., you find yourself standing next to him at the twenty-four-hour Chinese buffet while he builds a teetering pile of ribs on his plate. “Bones.” He pulls out a couple to prove his point. “Dry ribs. Were we at Fortune House last night?”

“I was here last night,” Charlie grumbles. There’s something about the way Martin looks today — something in the plum-coloured circles under his eyes — that’s making the pain in Charlie’s chest worse. Charlie and Martin have spent many an evening together when neither could find any good reason to go home. The night always ends with Charlie standing at the entrance to some downtown alley, yelling at a drunk-deafened Martin wandering off to something more sinister.

Their baker, Tara, hasn’t lifted her head off her knees yet. He gives her a nudge with his boot, but she doesn’t move. Rose stands next to Martin, smoking and chewing gum at the same time. “Like menthol,” she explained to him once. Charlie nudges her for a cigarette even though he has a nearly full pack in his back pocket. “No,” she says, scowling at him. She reminds him of a cigarette — skinny, dirty, stinky, but still appealing in a way he could never explain. She’s added to the sleeves on her arms, swirls of stars mingling with twisting koi tails. He glares at her tight-lipped, dagger-eyed face and vaguely recalls a remark he m

ade to her last night, something off the cuff, something about intelligence and a sack of bricks. “Don’t say no to me,” he says. She yanks out a cigarette and throws it at him. She’s the only one who refuses to call him Chef; she calls him Charlie, that is if she’s speaking to him at all. She’s above it: above taking requests, above scraping people’s leftovers into the garbage, and Charlie has a strong hunch she also feels she’s above him. He puts the cigarette to his lips without looking anyone in the eye. James, one of his kitchen runts, whips out his lighter. Asskisser, Charlie thinks as he leans the tip of the cigarette into the offered flame, catching the fire before a gust of wind blows it out. “Looking a little tired, Chef,” James says.

“It was a late night,” Charlie says. Rich, one of their First Cooks and an exchange student from Japan, beams at him. His hair stands straight up from his head and even in the wind remains immobile. Last night, he emptied the hot deep fryer oil into a plastic bucket, which meant Charlie was at the restaurant until the wee hours of the morning, drinking wine and jingling his keys while he watched Rich bop around the kitchen cleaning up the mess. The grease had melted the bottom of the bucket and poured out over the floor, also melting the bottoms of Rich’s shoes. It was difficult to get angry at him, because he spoke very little English and was also an unnaturally happy person. A bubble of chaos followed him wherever he went, and yet he was the only cook in Charlie’s kitchen who never cracked under pressure.

The cigarette doesn’t calm or ease the strain on Charlie’s lungs. He smacks his tongue against the pasty roof of his mouth. The birthday card has made him aware of a foul taste he suspects may be his life rotting away from the inside out. He’s parched, but he’s decided not to drink today. He wants to preserve an edge for negotiations. He hacks and spits into the ashtray can. “Fortune House,” Charlie laughs hoarsely, trying to distract himself from his thirst. “I was so stoned there one night. Was I with you?” he asks Martin.

“Could’ve been.” Martin smiles at the memory he may or may not have.

“The two-foot tower of chicken feet in the middle of the table,” Charlie says. “Did you help me build that?”

“Yeah, yeah.” Martin grins, nodding his head.

“This story again,” Rose says, rolling her eyes.

“What’s up your butt today?” Charlie turns to glare at her.

“You got kicked out. For some reason you were barefoot. You walked into a club, cut your foot, ended up in emerg, tetanus shot. Hardy, har, har.” She gets up, brushing dust off the back of her black pants and flicks her cigarette butt over the railing. “I’m fucking bored,” she says, stomping up the steps and slamming the back door behind her.

“Oh, stuff it, Rose,” Charlie calls after her, spitting into the garbage again. He briefly indulges a fantasy of flicking his cigarette butt into the bird’s nest she’s concocted with chopsticks at the nape of her neck. He imagines it stiff with hairspray. The fire would be quick, merciless.

Susan’s wife pulls into the parking lot and Susan climbs out of the passenger side, barely able to get the door shut before the car goes peeling out again.

“Finish the story,” Martin says.

“Naw,” Charlie says, with a shrug. “It’s been told.”

Susan strides toward them wearing a short skirt, a loose-fitting blazer, and sunglasses, even though the sky is dark with clouds. The consensus among the staff is that Susan is certifiably insane, yet people are still attracted to her in the way eyes are unwillingly drawn to an eviscerated creature on the side of the road. She’s only been at the restaurant for a few months, but Charlie already knows intimate details involving her sex life, gynecological exams, and bowel difficulties. She spent the last five years managing one of the top fine dining restaurants in Toronto, and her first week at Marinacove she walked around with a look of horror on her face — horror at the rude pops as wine bottles were uncorked, horror at the elementary way in which the napkins were folded, horror at the wet rings left from napkinless glasses. Her mission is to keep the bread-cutting board continuously crumbless. She keeps a razor in the back for the days when Martin forgets to shave, which are most days. She likes Rose for some reason, even though Rose is a terrible server, lazy and prone to rudeness and unwilling to carry more than two plates at a time due to weak wrists. Rose has to take air out back at least once a night, but never clues into the fact that her lightheadedness may be attributed to the serious lack in her daily caloric intake. She and Susan seem to share an affinity, though, for ridicule and laughter with a serrated edge. Susan’s laugh belies her fine-dining background; there’s something rough there, guttural, something that hints at small towns, strip malls, and truck stops. It makes for an odd juxtaposition with her shiny suits and blond-highlighted hair. Charlie pretends not to hear Susan calling him in her sing-song, sugar-drippy voice. This is not a good sign. Usually he and Susan mutually ignore each other. He smokes hurriedly and shuffles inside so he doesn’t have to say hello back.

As he clomps through the hall toward the kitchen, he accidently steps on Aisha’s ultrasound photo, which has fallen from the corkboard. She pinned it there for him when he admitted to not knowing how to tell the staff about the incoming baby. He stops briefly to rub a foot print off the paper and pin it back up, putting in an extra pushpin to hold the photo in place. He likes the corner picture best, the baby (or beast) staring straight at the camera with a hollow-eyed stare and mini-raptor’s hungry grin. There was some celebrating among the staff after Aisha posted the photo. The cooks were all overly enthusiastic, patting Charlie on the back and grinning at him like goons with that hopeful look he recognized as an expectation of free beer. Rose looked horrified and wished Aisha luck. Susan pulled two slim cigarillos out of the glass case on the bar and she and Charlie smoked them out back beside the dumpsters so their strong smell wouldn’t find its way into the restaurant.

“A father, eh!” Susan said, shaking her head and letting the smoke drift from her open mouth.

“Yep.” Charlie took note of his posture: taller, chest expanded, sturdy, reliable.

“My father was a fucking imbecile.” She laughed with that raspy tickle that unsettled him. He felt his body slacken under her words, his belly protruding to its natural state. He remembered what she was wearing that day: a tight-fitting white suit that glowed against the dirty grey of the back alley. She shone like a lesbian Madonna. He felt blinded by her truth — it was painful to the eyes. “You’ll be fine,” she said. “You’ll be better than him, at least.”

When Aisha told him she was pregnant he walked right out the door, down the hall, down the stairs, along the banks of English Bay, up the steep hill on Davie, into his favourite French bistro, and back down the hill on Davie before going home. He ate a piece of Alsatian pie at the bistro and felt miserable afterwards — he hated eating alone. In that entire length of time Aisha’s position on the couch and the expression on her face had not changed. She was gazing ecstatically into the maple tree outside their window when he left and she was gazing at the damn tree when he returned. Somehow he knew this meant she would not be leaving. It felt too easy; there was no discussion, no decision to be something new together. Their lives were running parallel and then all of a sudden they found themselves joined, two random atoms suddenly fused by a magnetic force.

AS CLOUDS AMASS, ROLLING in from the east, the sun is beginning its descent toward the ocean, shooting angles of light into the restaurant that reveal every single dust particle in the room. The windows were cleaned during lunch service and now someone’s poor job is illuminated, even streaks running the length of every window. Rose is carrying around a napkin and a steaming mug of hot water to buff the wine glasses on the tables. Martin wheels in a shopping cart full of booze and starts arranging the wine bottles and stocking the beer cooler. While he unloads the cart, he chats with Topher, the head chef of Adagio, an Italian fine-dining restaurant across the street. Charlie walks o

ver to the bar as Martin uncorks a bottle of wine and pours him a generous taster. “Here, try this. I’m thinking of adding it to the list.” Martin’s face is shiny after a fresh shave. There’s a nick above his lip that’s bleeding.

“Quiet in here today,” Topher says, as Charlie tips back his wine glass. A taster is not a drink; a taster is part of the job. Many years ago, before Charlie’s father had a heart attack, he employed Topher at his restaurant, Le Carré. Topher knew Charlie as a fat little boy who stood quietly, like a ghost, in the corner of the kitchen. “Tu es un fantôme, tu n’es pas ici,” his father would say. You are not here. When his father drank too much, Topher drove him home, and on those nights Charlie would wake to his father singing over the stove, swigging straight from a bottle of wine on the counter. “Viens. Viens ma petite bête. Mange avec moi.” Charlie was a little beast — a chubby, acne-pocked little beast. His father would stuff his face with cream-drenched noodles, layers of fatty meat, salty fries. He’d eat anything brought to his mouth: liver, blue cheese, tripe. At the age of eight, he already knew the difference between a béchamel and a velouté.

Clear Skies, No Wind, 100% Visibility

Clear Skies, No Wind, 100% Visibility