- Home

- Theodora Armstrong

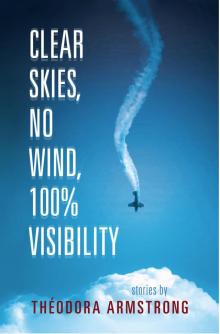

Clear Skies, No Wind, 100% Visibility Page 17

Clear Skies, No Wind, 100% Visibility Read online

Page 17

The last time we were all at the lake cabin was almost two years ago. Angie was pregnant but not telling anyone yet. Thom and I spent the weekend getting absolutely bombed, drinking whiskey and coke out of plastic cups and barbecuing on the beach. I was feeling celebratory — in sharp contrast to Thom, who was bemoaning the fact that I was dropping out as an unclassified student and moving to Cornwall to start flight service training.

“What!” Thom had said, shaking his head. “What a waste! But marriage will do that to you.”

“Thom, God! Please don’t start,” Veronica put her hand on Thom’s neck. It was hard to tell if she was going to strangle him or give him a massage. “Can’t we have a holiday without badgering? For once!”

“He’s not even part of a program, Thom,” Angie said. “Don’t be sad because your friend’s getting a life.”

Angie had spent the day in the lake, swimming, while I watched her from the dock, drinking. She’d aim straight, swim far out to some hidden point on the horizon. Eventually I was drunk enough to follow her into the water, my messy hands slapping the water like dull blades. I played that game with her, grabbing her ankles underwater and pulling her under, the game she hates, putting those messy hands all over her body, the smooth skin over her shoulders and along her neck, her waist, her thighs, my fingers running under the edges of her swimsuit. Later she leaned against me, legs stretched out on a chair in front of her, hair still wet, my hand resting on the inside of her thigh and twitching to move farther up.

“Marriage will do what to you?” I said. I felt like humouring Thom. I felt better than him.

“Smarten you up. Smarten you silly, maybe.” Thom smirked into his plastic cup. There wasn’t much left but ice. “We won’t be doing that song and dance.”

“Marriage is hardly a song and dance,” Angie laughed.

Veronica stretched her arms far above her head and yawned, making a point of being bored with Thom.

“Oh, it is. Mostly a dance, though.” Thom stood up from the table, curtsied and did a lively soft-shoe.

“Sit down, you idiot,” Veronica said, shaking her head.

“I think I’ll have another,” he said to himself as he opened the two-litre of coke with a hiss.

“Have a glass of water, Thom,” Veronica said.

“It really has though. Changed your whole look. The look of you.” Thom was staring at me across the table with disgust. “You’re a different person.”

“Fuck off.” I was smiling.

I felt sorry for Thom that night, and for Veronica too, because of her association with him. My pity grew out of Thom’s own pity, out of Angie’s secret and our own happiness. The entire scope of our lives together stretched out before me that night, clear as a backyard surrounded by a blanket of trees and a sky full of stars. And that night, sitting across from Thom, my hand on Angie’s thigh while she sipped her water with lime, I found it all incredibly funny.

I WAKE UP IN the chair in front of the computer and make my way through the dark house to the bedroom. Angie’s set up a fan in this room too, pointing it at the bed so the breeze makes ripples across the sheets. She settles herself closer to me as I get in.

“What happened?” she mutters into the pillow.

“She went right to sleep.”

“At work, I mean?” Angie raises her head and tries to find my eyes in the dark. She always seems to know when something is off. It will never be possible to lie to her.

“Water bomber crashed into the side of a mountain.” I lock my hands behind my head and look over at her. She’s in one of my threadbare shirts. It’s worn soft, with holes in the sleeves.

“Jesus.” Angie raises herself on an elbow. “Your call?”

“The whole thing was over in under a minute.” I lift up the shirt and run my hand over her stomach.

“You want to talk about it?”

“No.”

We have sex and we both come fast, which is the way it always is now, infrequent to the point of desperate mutual hunger. I come so hard it almost hurts, as though I’m being sucked right into her body, bound so tightly by her flesh I cease to exist. She asks me if it was good, better than any waitress I could get in town, and I laugh off the snarky comment. I tell her it was better than good.

Angie’s up and into the bathroom immediately, because of her recurring bladder infections, trying to piss out any unfriendly bacteria that might be trying to climb up her urethra. Usually, by the time she gets back in beside me I’m fast asleep — and those are the only nights I sleep well. But tonight I’m still awake, eyes-closed-pretending as she slips quiet as a mouse across the carpeted floor, standing stark naked at the window awhile to look out at our neighbourhood, dawn light behind the mountains, her hand pressed to her mouth as though she’s trying to stop something from escaping. When she eases herself back into our bed, I realize, for the first time, how careful she is not to wake me up.

THE LIGHT IS WHITE HOT through the curtains and the windows are closed against the noise of the neighborhood, but there are still reverberations — lawnmowers, motorcycles, children running down the sidewalk. The knock on the bedroom door is what woke me up and it comes again, louder this time. I sit up on the edge of the bed, groggy with sleep. The room is thick with heat, nearly airless. The fan is buzzing, jerking through its rotation. Angie pokes her head through the door with the baby on her hip and holds up the phone. She’s wearing shorts and nothing but a sports bra on top. “Work,” she mouths as I take it from her.

It’s the Transportation Safety Board. “We had a few questions for you regarding yesterday’s incident.”

“The crash?” I run my hand over the bedsheet. It’s damp. I feel over-rested, my mind in a fog. I try to rub my head out of its stupor. They’re calling to go over the data: weather information for five hours prior and one hour after the crash, audio records of radio contact, records from the navigational aids and radar. There’s someone else on the line, a voice that pipes in every once in a while to elaborate on a question or detail, someone’s name I didn’t catch. Everything they are checking is normal for any emergency, but now they’re asking me for a chronicle of all previous shift activity and an account of my sleep patterns.

“My sleep?” My voice catches in my throat, dry from the hot bedroom.

“The details of your sleep schedule over the past week.”

“Why?” I reach for a glass of water on the bedside table, take a sip.

“Have you been having any difficulty sleeping?”

“Sorry, am I being investigated for something?” Beside the water glass is a roll of antacids. I tear back the paper, pop a few in my mouth.

“These questions are procedural.”

“Procedural?” I rub the tingle of sweat on the back of my neck along the hairline and pop the window open, the racket from the neighbour’s mower flooding into the room.

“Normal for any investigation.”

“Oh, normal.” I take a deep breath out the window; the smell of cut grass. “All right.”

“Mr. Harris, have you been unusually fatigued this week?” I can hear the other voice talking to someone in the background. Somewhere in the house Angie is singing rhyming songs.

“Fatigued? No.” I crunch another antacid, chalky residue coating my tongue. “I sleep like the dead.” The words are out before I take the time to consider them.

“Can you think of anything else, Mr. Harris, that might help us with our investigation?”

“Anything of importance was submitted to you in that envelope. You should have everything you need.” I try to keep my tone even, but it comes off sharp and annoyed.

“If you think of anything else you can reach us at the office.”

“I won’t need to reach you.” I push the drapes back and bright midday light pours through the window. What time is it? Suddenly, it occurs to me

I might have slept for more than a night. Would Angie let me sleep for an entire day? Longer?

“Do you have any questions, Mr. Harris?”

“No,” I say, pulling the drapes closed again, a draft sucking them against the open window. “Actually, yes. How old was the pilot?”

I can hear papers being shuffled through the phone line.

“He was thirty.”

I thank them for their thoroughness and hang up the phone.

THERE’S ANOTHER CALL FROM the flight service station in the afternoon. Data that doesn’t correspond to the timeline and catapults me off the couch to scramble through drawers all over the house searching for some paper and a pen, the baby howling, startled by my abruptness, and Angie running her outside to walk the yard and calm her down. I watch them from the window, Angie pinching a yellow honeysuckle bloom free from the vine, holding it up to tickle Sophie’s nose. Everything right in the world. The supervisor must hear something in my voice, because he tells me — same as the TSB agent — this is standard protocol when a plane goes down. And why do they want my sleep account? He says the words again: standard protocol. He wants to know what kind of questions the TSB agent asked. I get him off the phone quickly without mentioning my worries, but there are things I’ve started thinking about ever since the call this morning. If I had exercised caution during that first communication with the pilot, advised him to land instead of wishing him safe travels like a fool, things could have turned out differently. There’s an empty aerodrome not too far from the crash site. There’s a field next to a high school nearby. I had to look closely at a map, but they’re there.

“Why do they keep calling?” The screen door slams as Angie comes back in with the baby, yellow pollen on her nose.

“I don’t know.” I rub my face in my hands. All day the extra sleep has hung over my head like the weight of a bottomless lake. “They’re going over the data. It’s standard protocol.”

“But what are they looking for?”

“How would I know that, Ange?”

“Shouldn’t you know?”

“I’m going for a walk.”

I intend to head for the forested paths behind the house, but as soon as my feet hit the front walk I lose steam and end up sitting on the edge of our curb, the sun barrelling down my back. The neighborhood is buzzing in the late-afternoon August heat, tinder-dry, vulnerable to any kind of spark. There’s been a water ban all summer and the lawns are brown and thirsty. There are thunderstorms in the forecast. From where I’m sitting I can hear the phone inside the house ringing.

IN THE MORNING WE prepare to leave for the cabin. On the radio they’re calling for a high of thirty-nine degrees Celsius. “Hotter here than Kuwait today,” I say, scanning the weather section of the newspaper.

“Maybe we should stay.” Angie’s leaning against the kitchen counter, arms crossed, holding her elbows the way she does when she’s willing to have a long talk. The baby’s in the playpen in the middle of the living room, ignoring us. She’s been fussy all morning from the heat. Angie says babies are sensitive to changes in a house. Somehow we’ve lost most of the day. At this rate we won’t reach Osoyoos until dinnertime.

“The car is packed.” I brush past her to fill my travel mug with the leftover dregs of morning coffee, but the pot’s empty. “Did you drink it all?”

“I’ll make more,” she says, without moving. “We can unpack the car.”

“I’ll make it.” I measure off spoonfuls. Pour the water. “Are you going to put on a shirt?”

Angie looks down at her sports bra. “It’s like a shirt.”

“No, it’s not.”

Early this morning I got another call, this time someone from the Critical Incident Stress Management team. It was a woman on the other end of the line, one of my peers, but the call was anonymous. The program is made up of a group of volunteer counsellors, people who have gone through similar incidents. I recognized the woman’s voice, but couldn’t place her. I asked her what she wanted to know, but she said she didn’t have any questions, just wanted to talk. I told her all I wanted to do was get a head start on my holiday.

“Why would we stay?” I ask Angie, folding the paper. The coffee machine starts spitting.

“Have you slept at all?”

“Yeah, I slept.”

In fact, I waited until Angie was asleep to pull out the maps again and spread them all over the kitchen table. I pored over the data, checking and double-checking, reviewing everything I knew to be true. There is an edge of doubt that seems to be wedging itself further into me. “Thom and Veronica are expecting us,” I say. “He barely leaves the house, you know.”

“Maybe we don’t need to be around that right now.”

“What difference does it make?” I throw some T-shirts into the last bag by the door. “We’re going to sit with our feet in the lake and drink beer.”

“Exactly.” She cracks a tray of ice and drops two cubes into her cup of coffee.

“Exactly?” I throw the duffel bag over my shoulder.

“I have a pretty clear idea of the way the entire weekend is going to go.” Angie sits down at the table and unfolds the newspaper.

“I’m taking this out to the car.”

THE HIGHWAY IS CONGESTED, cars packed to capacity, little faces pressed to back-seat windows, slack-faced boredom and wild eyes. In every car that passes I can see fights brewing like storm clouds sliding into a valley. When we got into the car the surfaces were so hot I could barely touch the steering wheel. Angie has been quiet since we left and just when I think she’s sleeping again she turns to me and asks, “Why do we always have to go somewhere on the long weekend?”

“Why would we stay home?”

“I don’t know.” She closes her eyes and rests her head against the window.

“You’re so tired all the time.”

“Too much sleep.” There’s a note of hopelessness in her voice, something I’ve heard before. Lately answers have been different between us, a slight shift, enough tilt to make a pencil roll off a table top.

“Maybe you should get that checked,” I say.

A few weeks ago Angie found a scrap of paper in my desk with the rough ideas for a poem sketched across it. It was something I’d done dead sober over a sleepless night, a few leftover thoughts from a poetry workshop I’d taken at university, scrawled so the words were barely legible. She was curious about it, excited by what she’d found, but for some reason seeing that paper in her hand made me feel shame. We had a huge fight. It was the white-paged honesty of it — the poem — that made me accuse her of being nosy, that made me say all sorts of insane things, that she was looking for girls’ numbers, that she thought I was heading to the bar after work to fuck waitresses. I told her that if I was going to get so much grief for doing nothing wrong, I might as well be fucking waitresses. We were standing in the kitchen and I stuffed the piece of paper into the garburator, barely getting my hand out of the hole before flipping the switch and setting the blades in motion.

“Look,” I say, checking Sophie in the rearview mirror. “She’s sleeping already.”

Angie’s taken off her shoes and placed a rolled-up hoodie behind her neck in preparation for the long drive.

“Close your eyes and sleep,” I say.

“I’m not going to sleep. I just don’t feel like looking at everything.”

After a while she asks me if I want to trade places.

“I’m fine.” I look over at Angie, but she stares straight ahead at an empty length of highway as though she hasn’t heard me. “I’m fine,” I say again.

“I know you are,” she says before closing her eyes.

THE LAST TIME WE saw Thom and Veronica was early spring. It was the first time they’d met Sophie — she was already nine months old — and Thom had looked stunned by her delicate hands and tiny teeth.

He stuck a finger in her mouth and she bit him.

That night we drank until the sun came up. Thom and Veronica rent the main floor of a ramshackle house off Fraser Street in East Vancouver. Above them lives a Korean exchange student and below them a construction worker in his early twenties. The air is always thick with the smell of kimchi and weed, and whenever I smell those two things I have an overwhelming urge to drink a large amount of beer.

In the backyard, Thom had set up two folding chairs on the plywood flatbed of the construction worker’s truck, with an overturned plastic bucket as a table between them. The girls stayed inside talking about whatever women talked about when there were no men around and Sophie was asleep on their bed, surrounded by a barricade of pillows.

“Your neighbour doesn’t mind you drinking on his truck?” I’d said, taking a seat in one of the folding chairs. There were cup holders for the beer.

“I’m letting him park in my driveway,” Thom said, passing me a can.

We settled back in our seats, the sounds of a city neighborhood around us, rush hour traffic down Fraser Street, ambulance sirens and the strains of Sepultura coming from the basement suite. I’d already grown accustomed to the quiet nights in Kamloops. Thom had dragged an extension cord through the yard and plugged in an electric campfire. It flickered as the night dimmed behind us.

Clear Skies, No Wind, 100% Visibility

Clear Skies, No Wind, 100% Visibility