- Home

- Theodora Armstrong

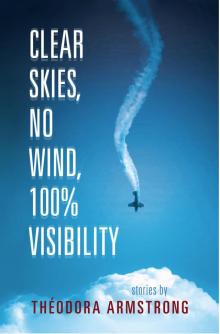

Clear Skies, No Wind, 100% Visibility Page 16

Clear Skies, No Wind, 100% Visibility Read online

Page 16

“Golf Foxtrot Zulu Whiskey. Mayday, mayday, mayday.”

“. . . into the side of the mountain.”

“. . . huge fireball west of Fintry Provincial Park.”

When the calls stop I get up and walk around the room, snapping the blinds one by one, yanking the thin little cords and sending them up so fast they crash and rattle into the tall windows. “I want to be able to see what’s going on out there,” I shout at no one in particular, to the whole room, launching my arm in a wide arc to account for every single one of them. “What the hell do we have windows for?” No one in particular looks in my direction. “And if it bothers you, John, wear some fucking sunglasses.” I slam the door and head for the vending machine glow at the end of the hallway. John follows me and at first I think he’s going to start complaining about the blinds again, but his approach is too slow, too careful. When he gets to me he stretches and his back cracks. “You good?” he says, without looking over, drumming a finger down the machine choices.

“Fine, yeah,” I say, fishing in my pockets for change.

“First one, eh?”

I look over at John, but he’s tapping his foot and staring at the vending machine, nodding his head as though it’s emitting some kind of musical beat.

“Well,” John says, considering the coins in his hand. “You’re part of the club now.”

“What club?”

A few months ago in a conference hall for a seminar on flow and capacity management, I sat in silence — the only person under fifty in the room — and sipped my acrid coffee, letting it burn my lips while I listened to all those grey-hairs add up their years to retirement. When I was asked to introduce myself, I stood and said, “My name is Wes Harris and I have thirty-three years until retirement.” The room thundered with laughter, all these rip-roaring red faces going berserk at the thought of thirty-three more years. They laughed so hard they cried, grown men wiping tears from their jiggling cheeks. I meant it as a joke, but for some reason I couldn’t laugh along with them. I sat back down in my seat. Sipped my coffee. They all looked the same to me, inside and out. It was the pallor of their skin, that waxy sheen and puffiness around the eyes after years on the job — the signs of a dull heart. I check my reflection in the screen for those signs. Pull down my bottom eyelids. So far I see nothing of the sort.

“Some guys go their entire careers without a call like that. Now look at you.” John slaps my shoulder. “Not even a year in and you’ve had your first.”

“Guess so.” I go to put a coin in, but John gets there first. “Is that something to be proud of?” I ask him.

“Had my first, oh, almost ten years ago now.” He takes his time choosing his pop. “My only, actually. Pleasure pilot with his wife. Oil pressure problem. Found the plane half-submerged, tail up near the beach. Just a few feet of water, but they both drowned. Mountain’d be quicker.”

“Sure would.” When I reach out to put my coins in I notice my hand is shaking.

“Why’s that grizzly sleeping on a cloud, right?” John chuckles, cracking open the can and taking a long sip. “Heard that one?”

“Nope.” I shove money into the machine.

“When’d they raise the prices on this thing, anyway?” He takes another sip and gives the machine a jab. “Another quarter and still the piss-poor selection.”

I punch random buttons. A can drops into the slot and I grab it and leave John standing at the machine talking to himself. When Angie was two months pregnant I flew to the other side of the country to train for this job, a year in a program with a 3% success rate — flashcards, mnemonic devices, simulators — studying day and night in a dorm room in Cornwall that smelled of feet (could’ve been my own feet.) But I ate it without complaints. Forget the fact that I could knock off a paper on the Islamic Golden Age over an all-nighter while half in the bag. I may have had a future on one of those leafy campuses, but instead I became a human mainframe for weather and word patterns. Alpha, Bravo, Charlie, Delta, Echo, Foxtrot, Golf, Hotel, India. That’s the versatility of the human brain.

Back at my desk the screens are winking and the condensation drips down the sides of the can, pooling at its base. After the sugar, my hands have steadied themselves, but my heart is still pounding in my chest, like waking up from a bad dream you can only remember the outline of. Sometimes you need some fire and brimstone to wake you up. I guess that’s where I am now, awake in front of all these buttons telling me things, giving me the answers. All I have to do is record and repeat. But the fire and the brimstone aren’t here, far from it. And in a funny way I feel nothing. After all that, I am still sitting at my desk, tapping my fingers on the particleboard. That’s what the training is for. The shaking is a symptom of the adrenaline. Juliet, Kilo, Lima, Mike, November, Oscar, Papa, Quebec, Romeo. I’ll get a phone call soon. I start to prepare the package. Everything that is recorded is kept, sealed, mailed, analyzed, investigated by the Transportation Safety Board. I pick up scraps of paper where I had scribbled details and set them aside to be included in the envelope. With the blinds pulled up the entire room looks different. John’s back at his desk rubbing his temples, making a real show of it. I take in the view from the windows: Cinnamon Ridge, the golden hoodoos under clear blue skies. No wind. Perfect visibility. A good day for flying. A host of sparrows lifts from the line of windbreak birches south of the tarmac, swooping in two giant arcs before settling back again among the branches.

The phone is ringing at my desk and I have a hand on it, but there’s that pause again — one second and a half. Sierra, Tango, Uniform, Victor, Whiskey, X-ray, Yankee, Zulu. On the tarmac a shimmer of heat blurs the ground and far in the distance — far as one can get it seems — off on the other side of those great blue mountains, smoke.

“LOOKS LIKE A HAWK,” Angie said, one slender hand shielding her eyes, the other resting on the baby nestled against her chest in the carrier. Sophie was four months old and it was late October, the air brisk and needles on the path, sticky with resin. The hike was a way to avoid the boxes stacked to the ceiling in our living room. NAV Canada had placed me in Kamloops and we’d just moved into a split-level rancher twice the size and half the price of what we would’ve found in Vancouver. We didn’t know anyone in the city. Everything was new and it was easy to be busy and happy.

“I’m going up,” I said, arms crossed over my heaving chest. I coughed and spit into the dirt.

“No,” Angie smirked, “you’re not.”

“I am.” My knee was throbbing and I stooped to rub it. I’d broken it several years ago when I fell out of a second-story window during a game of indoor paintball, and every so often after exercise or strange weather it would start to act up.

“Sore?” She smiled at me and bounced the baby from side to side. “Why don’t you catch your breath?”

“I’m fine.” I said, shrugging her off. We had reached our goal: the telecommunications tower up the mountain behind our house, the one whose red spire blinked above the tree line. The path snaked up the mountainside, keeping its grade gentle, but the distance was enough to get me huffing the cold air as I tried to keep up with Angie. Even with a baby strapped to her chest she was faster than me. I could tell she was staying ahead on purpose, trying to make it look easy, but there was a shimmer of sweat on her upper lip. On the way up, we’d talked about ways in which to build a new life. It was difficult to say who had asked more from the other coming here — Angie, giving up the possibility of returning to her counselling job, or me, venturing into a whole new career. On any given day it felt different.

I bent down and took a few deep breaths.

“You know, it isn’t a race,” Angie said, sitting on an old rotted-out log covered in moss.

“Sure it is.” I winked at her and climbed the first rung, feeling the joints of my bum knee grinding together. The hawk was perched about halfway up the tower.

“You

’re an idiot.”

“Well, you married me,” I said, adjusting my hands to get a better grip, “so what does that make you?”

“A charitable soul.” She sounded tired even though I’d let her sleep through the night and well into the morning. “Please don’t kill yourself to impress me.”

“Oh, I know little I do will impress you.” I took another step up. The rungs were far apart and it took a bit of a push to get up to the next one.

“I can tell from here it’s a Harlan’s hawk.” She leaned back on the log and tilted her head to the sky.

“Well,” I said, looking down at her. “That, from a city girl, does impress me.”

“I know some things.” She got up from the log and brushed off her bum. “Okay, Wes. Let’s go. You’ve had your fun. I’m ready for some lunch.”

I ignored her and kept climbing.

“Wes! For real now. I’m not kidding around.”

I’m not sure what sent me up that tower. It was the hawk, at first, and curiosity, but once I started climbing there was an excitement and an anxiousness that kept me going. With each step my limbs felt more capable and my heart felt larger. I had an ear-to-ear grin that usually only struck me after beer number seven. I figured out a system to scale the tower using the diagonal red lattices to boost myself, and climbed to its mid-point quickly, waving down at Angie every few minutes. She didn’t wave back, but stood on the log, hands on hips, looking pissed. I knew what she was thinking: stupid little boy. And I grinned that ear-to-ear smile down at her exactly like a stupid little boy would.

As I got closer to the hawk I slowed down, remaining still for several moments before ascending the next section. The hawk didn’t move. Its brown feathers glinted with flecks of gold as it scanned the valley, head turning slowly from side to side. I’d taken one step closer to the bird, watching it from little more than a foot away, when it launched itself into the sky. I could hear the click of its talons and feel the wind from the beat of its wings as it set in motion. As the hawk glided down the mountain above the treetops, I took in the entire expanse of the valley — like a dark green bowl turning on a table top. Angie was pacing below the tower now, yelling obscenities and waving her arms, but I was conceivably high enough to be out of earshot. Tilting my head back, I hooted like a pimply-pocked teen out a car window, and even from that height I could tell Angie was rolling her eyes. I leaned out from the tower, brandishing one arm and one leg through the air, and called down to her, “I can see our house.”

The bird was almost out of sight when my knee gave out. All the words I was hurling were suddenly trapped in my throat and every cell in my body focused on the one hand that gripped the cold steel. It happened so quickly Angie didn’t even notice. I waited for a shriek or some kind of commotion from below, but all I could hear was my own panicked breathing. The contents of breakfast, scrambled eggs and buttered toast, sloshed around my stomach. I flailed until I found footing and my other hand found a grip. I closed my eyes against the valley and breathed deeply as I steadied myself, the hawk the only image gliding through my brain. My sweaty hand could have lost its grip and I could have ended up a crumpled mess of bloody bones at Angie’s feet, but what I saw was freedom, the hawk vanished into the vast envelope of trees.

I started down slowly. Every few minutes Angie would call up to me:

“It’s starting to rain.”

“Harder coming down than going up, eh, smart ass?”

“Sophie’s waking up.”

“It’s going to pour soon, I think.”

Later that night on the Floor I had my first urge for a taste of that freedom. I was two months into my new job and I’d memorized the dates of every holiday for the rest of the year.

I didn’t realize how close I was to the ground until I felt Angie’s hand.

“Don’t worry, I got you,” she said.

“I’m fine.” I shook her hand off my ankle.

“I got you.”

“I don’t need you to get me.”

OUTSIDE THE WINDOW THERE’S a black sky and evergreens even blacker beyond the perimeter of the backyard fence. The trees surround the valley; the city feels insignificant, almost unwanted. I feel unwanted. None of it holds a thing for me, not a memory or a future, and it’s peaceful in its emptiness. What are your intentions? The question comes from some dark corner of Sophie’s bedroom. Even with the fan whirring in the corner, the air in the room is oppressive. I close my eyes and hold Sophie against my chest, rest my chin on her damp head. In the baby’s room during the blackest hours of the night I can breathe, stare out the window, smell her hair, and let my mind bottom out. It’s like turning down the static on a radio.

“What are you doing?” Angie’s standing in the doorway naked, her head a mess of dark curls.

“Didn’t you hear her?”

“I heard you.” She crosses her arms and leans to take a look at the monitor.

“She was crying,” I whisper overtop the baby’s head.

“I didn’t hear her.” There’s skepticism in her voice. I’m almost always the one to get up with Sophie in the night. It’s my way of making up for those four lost months while I was away at training, but for whatever reason Angie doesn’t trust my effort. She’s told me none of the other dads are so willing. She feels the need to lie to the other parents and feign exhaustion. She gets a solid eight hours every night but still guzzles coffee all day long.

“Sh!” I hold a finger to my lips.

“I must be wiped out.” She tousles her thick dark curls until they nearly stand up on end. “How was work?”

“I’ll tell you later. You’re naked.”

“It’s hot.”

“Go back to sleep.”

Out the bedroom window, the apex of the spire has a blinking red light. What are your intentions? I’ve barely thought about the pilot since sealing the envelope of data for the TSB, but now the question is nagging me. I hear my own voice, cold and flat as the computer teller at an automated checkout. The crews probably won’t have had time to recover the plane tonight. The valley isn’t easily accessible and there are spot fires all over the region, making a recovery dangerous. It could be days or weeks before they find anything, depending on the fire’s temperament. When I was a kid we used to watch the bombers flying low over the Okanagan Lake. They travelled narrow valleys other aircraft never flew, their planes heavy with cherry-red chemical water, flying through thick smoke at treetop level and dropping their payloads right over the tips of the burning evergreens, then suddenly rose — lightened and askew — toward the sky. Some summers the edge of the mountain was like one long flickering orange ember at night. I met a few of those guys going through orientation. The pilots accepted the dangers of their job and some of them lived for it. Some of them would pray for a fire so they could bomb. Otherwise, it was sitting around twiddling thumbs. Rapping their knuckles on particleboard desks, waiting for something to happen. It’s not that they wanted the forest to burn, but there was an itch there they couldn’t ignore.

I put Sophie down and head into the living room. Angie has fans in every corner of the house, a small one spinning on the kitchen counter and a standup pointing out one of the open living room windows, sucking the hot air out of the house. The only movement in the room comes from the propellers and the screen saver on the laptop, a twirling planet in a black cyber sky. I sit down at the computer and find a new message from Thom headed: The Useless Bungling of Wes’ Own Ineffectual Life.

The new message reads: Dear Asshole, have you ever considered the fact that my very purpose in life is to be the existential thorn in your side? You left me with no choice since the day you cut off your own balls and became a so-called reasonable adult.

For the past week, he’s been trying to convince me to call in sick so we can meet up in Osoyoos a day early. The lake cabin has been a summer ritual since we met

in first year. The message goes on to question, for the hundredth time, my decision to flee Vancouver for Kamloops and leave him to drink cases of beer all by himself. He blames me for the broken coffee table and overflowing recycle bin.

I reply: Dear A-hole, have you ever wondered if the reason you seek my company is that you cannot, for even a single moment, stand yourself? This is the nature of our relationship.

When I met Thom we were both first-year students at the University of British Columbia. After our English classes we’d end up at the same pub and eventually we ended up at the same table. I was with him the night he met Veronica at an art show in the student union gallery. She was showing some photographs and we had stumbled in at the sight of free food on our way back from the pub. Thom spent the entire night standing at a table stuffing his mouth with spinach phyllo pastries and drinking glass after glass of cheap red wine in plastic cups, wine he knew would make him angry enough to kick over every garbage can he spotted on the way back to his place. Veronica went home with him despite it all. She says she likes to photograph his tragic face. When they say goodbye, she grabs him by the chin and pushes his lips into a pucker she kisses. Mornings she wakes him up by straddling him and taking his portrait. “For a project I’m building,” she says. Twice he’s had to shell out a considerable amount of money for broken lenses after he wacked the camera out of her hands in a groggy, flash-stunned confusion. It was Veronica who introduced me to Angie, made her appear at our table one night as if by magic. She said, “Wes, this is my friend Angie. You don’t want to fuck this up.”

Mostly Thom is happiest lying on the rotten sofa on their front porch, smoking weed and reading. The two of us never talk about work or offer details of our day to day, and in that way we can exist together in a world separate, a world perhaps a bit loftier, a bit brighter than the one we live in, a life we would have dreamed up after a lecture in Comparative Literature and a row of pitchers at the pub. Occasionally — though I can’t be sure — I think Thom forgets I have a child. He likes to talk about ideas. He likes to argue — is happiest, even, when arguing. He likes to remind me that I wasted my MA and subsequently my contemplative life. He likes to remind me that he can drink me under the table. This is the way I see Thom at this very moment: in his living room, pacing the creaking floorboards, practically climbing his bookshelves stacked with the Western canon, fist in the air for reasons fair or concocted, a neat row of beer bottles arranged in patterns along the coffee table, trying to engage in debate the figure of his girlfriend hunched over a computer, photo editing. He’ll argue with himself, if no one else will listen.

Clear Skies, No Wind, 100% Visibility

Clear Skies, No Wind, 100% Visibility