- Home

- Theodora Armstrong

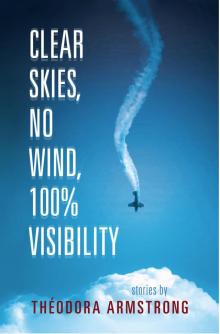

Clear Skies, No Wind, 100% Visibility Page 5

Clear Skies, No Wind, 100% Visibility Read online

Page 5

“Maybe look on Salt Spring.” She smiles at him. “Sorry, Dad.”

“What are you sorry for?”

She sits up and tugs self-consciously at the back of her sweatshirt, trying to cover the gap of bulging flesh above the waist of her jeans. She’s dwarfed by the sawed-off tree, sitting like a little girl, with her knees tucked into her chest. He gives her a gentle pat on the back. She shrugs her shoulders. “Nothing, I guess. I wanted to like it too.”

He rests his arm across her shoulder for a moment and then pulls her close in a hug.

“Dad,” Leslie says, laughing uncomfortably, “you’re squishing me.” He pulls away and they sit quietly.

A wind passes through the trees, picking up Leslie’s hair as though she were sitting at the bow of a boat. It moves the branches of the huge firs and gives the two of them a better view of the ocean.

THEY DECIDE TO GO home early. Anna stays in the bathroom until Ted is outside honking the horn, and when she comes out they barely exchange a glance. The girls sleep during the ride back to the harbour. The thick smell of a night of drinking hangs in the car and Ted rolls down the window for some fresh air. The ferry shakes as it pulls away from the dock. A tugboat presses along beside them, a sort of sentinel, heaving headfirst into the oncoming waves. It rides each swell to its crest, suspended for a moment mid-air before plunging down the other side in a wake of white foam. The island is still covered in mist, still circled by a grey ocean. The fog has lifted slightly and the rocky shores are visible, littered with washed-up logs; their gnarled branches and stumps look like limbs and torsos in the muted light.

Ted looks up into the rearview mirror and catches Anna watching him. Fear flickers across her gaze, changes her entire face for a quick second, and scares Ted enough to catch his breath in his throat. He looks away, and when he looks back Anna’s eyes are closed. Her face is new in a way he can’t identify; there is something unrecognizable there. He can hear the nasally inhale of her breath, the feather-light rasp he’d never detected before, the sound like an engine rattle to him now, a broken-down thing. She looks so serene he can almost convince himself he imagined her eyes opening and all along she’s been sleeping peacefully.

As they unload from the ferry, Ted holds his breath.

BACK ON THE ISLAND HIGHWAY the rain starts again. Ted turns on the windshield wipers and the CBC. He opens the window a little wider and takes deep breaths of the wet, evergreen-filled air. The mountains are still covered in patches of snow, but the poplars are dripping with red catkins. He decides not to tell Heather about the weekend, about Anna. He’ll tell her the property was a dud. He’ll tell her the girls enjoyed the fresh air, they should get away more often, next time Heather should come. The rain turns hard and Ted rolls up the window, clicks the windshield wipers to their top speed. He’ll say those things, but he won’t believe them. This will be the last time.

A transport truck approaches in the rearview mirror and passes them on the left. As it overtakes them, the car rattles gently. He’s aware of the weight of the steel chassis, the spin of the tires, the phantom feeling of impact. The truck’s wake kicks up a slap of water against Ted’s windshield as it shuttles past. Even though he anticipates it, he still jumps. He’s blinded for a few seconds. The wipers go swoosh, swoosh across the glass. And just like that, everything slips away.

WHALE STORIES

THE SCRATCHING OF THE pine needles on the roof woke William from a dream that left his armpits damp. The wind crawled through the trees, weighing down the boughs, forming fierce patterns on the wall above his bed. An empty pillowcase tacked up with two pushpins covered the bedroom window. His mom hadn’t found time to buy curtains yet. They didn’t have a kitchen table or a TV or a couch or a doormat. The bed and breakfast was bigger than their house in the city, and for now most of their furniture went into the guest rooms.

There was something else — another noise, some sort of animal snuffling and pawing at the side of the house. Shaking himself out of his covers, William flipped on the bedside lamp and checked the alarm clock. It was already nine-thirty. He pushed the pillowcase aside and opened the window an inch. The wind cried through the crack, spitting salty air into his face. There was a clatter of garbage cans below and he caught sight of a scruffy tail disappearing under the porch: one of the wild dogs again.

At the end of the yard, the huge arms of the pines rolled like they were trapped in an underwater storm. The clouds collected in dark barrels along the mountainside. He could see a small section of the beach through the thick cover of pine trees, the waves reaching up, breaking, and then dropping onto the grey sand. William yanked the window shut, rattling his rock collection, which sat in a tidy line on his windowsill. The rocks came from Australia, Africa, South America. His father was a geologist and travelled all over the world collecting samples from the different continents. The travertine rock — William’s favorite — fell to the floor, ricocheting under the bed, but he had no time to find it this morning. He dressed quickly, pulling on his dark blue sweatpants and a grey sweater. He had planned to be up hours earlier, before his mom and his sister, but he hadn’t slept well last night. He kept hearing footsteps and voices in the upstairs bedrooms. He still wasn’t used to the B&B, the strangers in the house moving around at all hours. The floors were rough and creaky, and it took him a while to figure out how to sneak around soundlessly. When the guests left for their daily outings he would open the doors to their rooms — something his mother had warned him not to do. He only ever took two and a half steps into the room and from that point craned his neck to get a look inside their suitcases.

In the mornings, William’s mom left their breakfast on the kitchen counter or in the oven to keep warm while she bounced back and forth from the kitchen to the dining room, serving the guests. Her cheeks were always pink and she smiled widely, with only a small crinkle of concentration on her forehead. She did look happier to William, but only when she was working, cleaning up or listing the best spots to go kayaking. The guests came from all over — Ohio or Toronto or Oslo. His mother told him once that instead of opening their home to one traveller — his dad — she could now open it to all of them. William sometimes felt like one of his own rocks but much bigger, rooted in the middle of the ocean, with people from interesting places drifting past on their way to somewhere better. His mother kept saying this was her dream, something she never could have done if she was still living in the city with William’s father.

In the kitchen his younger sister, Miriam, sat on a chair, her plate of waffles balanced on her knees, the plate looking dangerously unstable each time she cut herself a bite. William could tell Miriam had already spent most of the morning outside. Her jeans were grass-stained and she was wearing her yellow rain hat. This was probably her second breakfast.

“Where are you going?” she said.

William grabbed a waffle from the counter and ate it standing up. “To the beach.”

“It’s going to rain.”

William shrugged.

“Why do you have to go to the beach every day? I found a hollow tree. Just past the road up there,” she said, motioning behind her with her fork.

“Good for you,” William said, stuffing the rest of the waffle in his mouth.

“I can show you where it is.”

William ignored her, gave her a half-hearted wave goodbye, and headed outside, grabbing his pocket knife before shutting the kitchen door. He kept it hidden in his rain boots by the coat hanger. His father had given him the Swiss Army knife last year on his ninth birthday. It had come all the way from New Zealand in a large yellow manila envelope with his name written in big capital letters across the front. His mom and dad had fought about it over the phone, about whether it was an appropriate gift for a boy his age.

The wind tugged at William’s wet hair and crept up the sleeves of his sweater, sending a shiver down his back. He took the por

ch steps two at a time and bounded for the forest. Now the tree trunks swayed back and forth, their bare, spiky tips slicing through the dense fog billowing off the ocean. Usually it took him a while to cover the distance between his house and the water’s edge because he often stopped to watch a beetle’s progress or to unravel the tight coil of a worm with his finger, but this morning he hurried along the path, anxious to get to the beach. William scowled as he hurtled past one of the B&Bers standing in the backyard — a birdwatcher with expensive-looking binoculars. He couldn’t understand why his mother loved to share their space with these strangers. Back in the city, they’d had a large, fenced-off yard where there were never any birdwatchers getting in his way or little kids wanting to play little kid games or kayakers flapping around in the water like angry birds. Whenever there were children staying at the B&B, his mother coaxed him and his sister into playing with them. Miriam seemed to like the other children, drawing them into make-believe games in which she often chased them, pretending to be an elephant or a rhinoceros. Miriam, in fact, seemed lonely and sad when the children were gone, but William preferred to be alone. Most of the time the children were much younger than him or had no interest in rocks or traps.

First thing to do this morning was to sharpen a stick. William wasn’t sure why, but he had a feeling. The wind had knocked down lots of branches, so it wasn’t hard to find a good one. He positioned himself on a rock with the branch laid across his legs and whittled the wood to a sharp point. A ragged dog, its grey coat matted with dirt and burrs, ambled over. William stiffened as the dog sniffed at his stick and his feet. He was wearing sandals and the dog gave his bare toes a lick before trotting toward the beach.

The dogs were a problem in the area. His mom said it was probably cottagers bringing their pets on holiday with them. Maybe the pets ran away or the owners were cruel and didn’t want them anymore, but the dogs were left behind. They bred and there was a pack of them now, all mutts, dogs turned wild. He never touched them. Many of them had sores or bits of their ears missing. Their eyes were shifty and they panted even when they weren’t running. Usually they left people alone and you’d only see them when they went rummaging through the garbage cans. At night it was hard to tell them apart from the coyotes. William was sure he sometimes heard them following him through the woods or watching him while he was on the beach. Some of the other residents would shoot the more troublesome ones, but no one really felt good about that. There was always a lot of talk in town about what to do about those damned dogs. Everyone called them those damned dogs. Even his mother, and she never swore.

The second thing William had to do this morning was to check the hole. He walked up the beach toward the rocky outcrop to the west, whacking with his new spear at the tall ferns that grew on the outskirts of the sand. The waves had left deep tidal pools along the rocks and he splashed through them, scattering tiny fish and sending crabs scuttling to their hiding spots. He loved the sound of their legs scratching across the boulders. On any other morning he would have stopped to peer into the puddles, maybe sent Miriam for an empty ice cream bucket so they could collect specimens. Miriam was meticulous about it, counting each crab, noting the ones that were missing legs or had odd markings, and giving each one a name. But this morning he was in a hurry. He wanted to get to the hole as quickly as possible.

He had visited this part of the beach every morning since they moved to the Sunshine Coast. It had taken him a long time to dig the hole. And it had taken him a while to pick a good spot. He chose an area protected by a rocky outcrop that stretched right into the ocean and hid the beach from view. He dug a couple of small trial holes and decided on a spot near the treeline where the sand was still damp but where the hole wouldn’t fill with too much water. The first week he started digging right after lunch and only stopped when it was dark and he could hear his mother’s voice yelling bedtime. He had worked straight through the noon heat, taking breaks every fifteen minutes and running into the ocean to splash water on himself. In ten minutes he’d be dry again and by the end of the day his body would have grown a second, salty skin. The first week had been hard work.

The second week it rained and he was down in the hole every day with a bucket trying to keep it from caving in. He found an old abandoned shed back in the forest. It was covered in moss with half the roof sunk in and the windows thick with spiderwebs. He pulled some old boards from the siding, dragged them through the forest, and propped them up along the sides of the hole, trying to hold up the walls. Since then, luckily, there’d been a dry spell.

In the third week, with the weather hot and sunny again, the hole was deep enough that it provided a little bit of shade while he worked. The challenge in the third week had been getting in and out of the hole. One day he had dug so fast and deep that he couldn’t get back out. For a while he had been convinced he had captured himself. He screamed for ten minutes straight and no one came. Then he sat and cried for another five. He imagined Miriam peering down at him with all her questions and then going to tattle — or worse, the B&B kids wandering over and staring with their googly eyes. They would think he was some sort of treasure or a wild sea creature, wet and thrashing, trying to get back to the water. Finally he discovered he could claw his way out, but that meant partially refilling the hole.

The next day he rigged a long rope he found in the abandoned shed to a nearby tree and used that to get in and out. The rope was dry and brittle, but it held. When the hole was deep enough — almost two feet taller than William — he covered it with large branches. He warned his sister not to go to that part of the beach. He told her there was a dead whale with its eyes pecked out, and that it stank so bad you would throw up on the spot if you went anywhere near it. She kept away from the whole area, but every few days she would ask him if the whale was still there. He would tell her about the carcass in different stages of decomposition: the tail munched away, the fin all droopy and slimy, crabs happily eating away the huge whale tongue. Miriam would listen to his stories and wrinkle her nose. Sometimes she’d gag or pretend to plug her ears. One day, he guessed, the whale would disappear and he wouldn’t have to lie anymore.

He never worried about his mom wandering in that direction. She liked to walk east, probably because it wasn’t so rocky. The beach stretched out smooth and glossy at low tide, as if the land and water were one. William’s mother warned them to be careful walking out on the sand. The ocean could be tricky, could sneak around you until you were left standing on an island, alone. Miriam had become uneasy about this and kept one eye trained on the ocean at all times when she was looking for shells.

Their mother’s walks were a habit now and came after dinner without any announcement. Miriam and William were never invited along and knew not to ask. For the first few evening walks, Miriam would clutch the porch railing and cry, believing their mother was never coming back. But now they barely blinked as she quietly escaped the house. Every once in a while, though, William still followed her, but always at a distance, watching her from the forest. He would crouch behind the tall ferns, his breath shallow and painful in his chest. She stopped at a different spot every time, and when she found her spot, she would sit on the beach and sink her hands deeper and deeper into the sand, staring out at the water. Sometimes she sat for a couple minutes and sometimes she sat for an hour. The longer she sat at the beach, the greater the chance she would cry. When she was finished, she stood and wiped off her bottom, but with her hands covered in sand she usually just made it worse. There was always sand in the house. She made William and Miriam take off their sandals and hose off their feet before they came in, but she never noticed when she tracked the sand in herself.

For the past two weeks, William had been waiting and hoping. He hoped that at least something small would fall into his hole, and if he was lucky something bigger. He wondered about the hole at night when he was in bed. Sometimes the wind tricked him and he thought he heard a yelp or crying. On thos

e nights he hardly slept, waiting for morning to come so he could go check out his catch, but there was never anything in the hole. A few nights earlier, he had an idea that came from watching one of the B&Bers fishing that day, something important he hadn’t thought about before: the hole needed bait. While no one was watching, he slipped the rest of his bits of beef from his dinner plate into the pocket of his shorts, and while his mom took her after-dinner walk he ran to throw them on the branches covering the hole. He’d done this every night for the past three nights: chicken, fish, and last night, pork.

William had dug a hole once before, when he was much younger. Actually, it was his father who had done most of the digging, with a small plastic shovel that came with the beach set his mother had bought for him. They had gone to Spanish Banks for the day. His mother was pregnant with his sister and lounged on the beach blanket his father had set up for her under a tree. William spent the entire day running back and forth between his parents at top speed, helping his father with the digging and pressing his ear up to his mother’s belly. His dad kept saying, “We must be on our way to China.”

That night his dad had to explain that China was actually very far away and that it would take years of digging to get there, that it was much quicker to fly or take a boat. But William was disappointed. He felt misled. Looking now at the speckled rocks half-buried in the sand, he tried to remember where his father was at this moment. Digging somewhere in New Brunswick, he guessed. He was fairly sure that was the last place. When they moved, they left all of his father’s clothes and books. His mom said it was easier for their father’s work if he left his things in the city.

“HI,” A SMALL BOY said.

William had been planning his attack should he find something in the hole, and he almost walked right into the kid. The boy was definitely one of the B&B guests and a couple of years younger than William — young enough that his parents still dressed him. William could tell by the way the boy’s shirt was tucked in and cinched with a miniature belt. His hair was carefully combed to the right side of his forehead. He was in gumboots, standing ankle-deep in a tidal pool, pushing around a large bit of Styrofoam with his foot.

Clear Skies, No Wind, 100% Visibility

Clear Skies, No Wind, 100% Visibility