- Home

- Theodora Armstrong

Clear Skies, No Wind, 100% Visibility Page 3

Clear Skies, No Wind, 100% Visibility Read online

Page 3

“Oh right, when I was like three,” Anna says.

“I wasn’t even born yet!” Leslie laughs and punches the seat. “Yeah, Dad. I remember that trip. I was in the womb. It was warm and red. It was a great trip!”

“Oh, come on,” Ted says, and he laughs too.

Leslie hangs out the window again and shakes her bum in Anna’s face. Anna gives her a hard smack on the butt cheek. “Bitch,” Leslie screeches and the muscles in Ted’s neck tighten. “Leslie, get in,” he shouts. She ducks back into the car, her face speckled with raindrops that she wipes away with the sleeve of her sweater. Ted fumbles for the keys in his jacket as the brake lights of the car in front of them light up and engines rev. “Okay, we’re off,” Ted says, turning on the car and taking a sip of his coffee. His headache has gone from dull to throbbing. He’s hit with the sudden wish for a couple drops of whiskey to sharpen the taste of the drink, anything a little stronger. He thinks about the four bottles of wine tucked into the cardboard box of provisions in the trunk. The car in front of them inches forward and the driver behind them honks.

“Dad, oh my God! Go already.” Leslie gives the front seat a hard kick and lets out an annoyed sigh. “Jesus, Mary and Joseph,” she says and then bursts into giggles, turning to Anna for a reaction. The car honks again.

“Asshole,” Anna says, under her breath. She wipes away the condensation on the back window and gives the driver the finger. Leslie bites her lip, cheeks puffing out again as she tries to hold back her laughter. Ted gives Anna a look in the rearview that says mind your sister, but he can’t help a smile.

As they cross the loading ramp onto the ferry, Leslie holds her breath, her face turning pink, and for several seconds there’s silence in the car. She slaps Anna’s knee to encourage her to do the same, waving her arms above her head insistently. Anna’s gaze remains fixed on the lineup of cars ahead filing onto the ferry’s deck, but Ted hears the sharp intake of her breath. Beneath the loading ramp the dark water surges.

Whenever they cross onto a ferry, everyone in the car is supposed to hold their breath — this is their strange family ritual. The girls created the game and when they were young Ted played along, but he doesn’t bother anymore. They invented it so long ago they’ve forgotten its origin, but Ted remembers. As they pull onto the deck Leslie exhales dramatically. A young ferry worker motions for Ted to roll down his window. “We’re going to get you in a little tighter,” the boy says. Ted backs up the car and pulls hard over to the right. “How much room do I have?” he calls out the window. “You’re good, keep it coming,” the boy says, and taps the hood of the car when he’s close enough. The girls are quiet again and Ted catches them staring at the boy. He’s around nineteen and smiles at Anna as he walks by. Ted turns in his seat to give the boy a harder look. “What are you girls staring at?”

“Nothin’,” Anna shrugs and Leslie turns a shade of red.

The ferry shudders to life and pulls away from the dock.

“I’m stuck,” Leslie says, looking out the window. “There’s no room to open the door.”

“It’s a ten-minute ride,” Ted says. “Close your eyes and we’ll be there.”

“But I want to get out!” Leslie rattles the door handle.

“There’s no passenger cabin,” Ted says. “Everyone stays in their cars.”

“I want to walk around,” Leslie whines. “My legs are cramping.”

Anna scrambles through the space between the two front seats and slumps down in the passenger side, bringing an arm up over her face. The skin of her forearm is translucent, a flawless white threaded with blue veins. “Seriously,” she mutters. “She doesn’t shut up.”

“We’re going to have a nice weekend,” Ted says, tapping Anna’s knee lightly.

The rain has stopped and the island is circled in a thick mist hanging low along its shores, the green hump of its back breaching the haze like a whale surfacing. Leslie is finally quiet and Ted, the full weight of the workweek suddenly hitting him, leans back in his seat and closes his eyes.

Many years ago a minivan plunged off the loading ramp of a ferry leaving Tsawwassen. There was a reason Ted couldn’t remember: rough waters, a careless worker, a mechanical malfunction. The van sank in the deep water where the ferry berthed, and got trapped between the massive hull of the boat and the barnacled underwater pillars of the dock, making the rescue difficult. There was a family inside: three children, a mother, and a father. The father was the only one who survived. He managed to pull out one child, a daughter, who died later in hospital. It took them several hours to haul the minivan to the surface. What could anyone do? A car fills quickly. Water makes movements slow. A scramble over the seats takes forever, like a thick-limbed nightmare. Ted can’t imagine the feeling of failure that must haunt that father. Heather used to use the story as a warning, a way of keeping Leslie and Anna quiet in the back seat. That’s when the girls started holding their breath.

OVER DINNER LAST WEEK, Ted told Heather about the property. He recounted Jim’s description of the five acres of untouched land, the hundred-year-old trees, the salmon fishing, the cliff that drops into a clear, calm bay. He didn’t tell her about the weathered Adirondack chair he imagined set near the edge of the cliff, where he could have his morning coffee and look out at the ocean — he kept that one for himself.

“What do you think?” Ted said.

“Sounds like an oasis.” Heather picked up her fork and poked it around the plate without picking up anything.

“I could use a new project.” Ted leaned back in his chair, hands behind his head, and looked around the room. “There’s not much left to do around here.”

“Sure,” Heather said, raising her eyebrows in agreement. “You like to be busy.”

Ted and Heather own a house in Fairfield, a three-bedroom revamped 1920s heritage home on Wildwood Avenue, a short drive to Gonzales Beach and Beacon Hill and an easy commute to Heather’s dental practice and his office in downtown Victoria. When they moved in, Heather had the house repainted and chose an imperial green with a red trim for the windowsills and front door. It’s not a colour Ted would have chosen, but it’s grown on him and suits the neighborhood, and he has to admit the house looks exceptional during the holidays. His favourite part of the day is the short trip from his car to his front door; along the walkway, with a quick stop at the mailbox, the clack of its little metal door, and up the steps until the moment his feet rest on the welcome mat.

“I think I’ll take the girls with me,” Ted said. They had stopped eating, but their plates still sat in front of them, the food long gone cold and both Ted and Heather too tired to clear the table. Anna and Leslie had excused themselves. From upstairs, pop music blared, commingling with the sound of the television downstairs.

“Would you like to come?” he said.

“Pardon?” For the first time during the meal, Heather looked directly at him. Sometimes he had the urge to reach out to her, give her a shake, shout: Wake up.

“Sorry, I was thinking of something else,” she said, scraping the food to one side of the plate.

“Can you get time off work?” Ted popped a cold carrot into his mouth, not because he wanted to eat it, but for something to do. He had the urge to spit it out, but realized that would be ridiculous and instead held it in his mouth for a moment before crunching through it and swallowing. The carrots were undercooked.

“Maybe,” Heather said. “Although I could get some stuff done here while you’re gone.” He didn’t picture Heather getting stuff done. He pictured her making tea and wandering around the house, forgetting her half-empty mug somewhere to get cold and heating the kettle all over again. He imagined cold cups of half-finished tea all over the house. He had a suspicion she was cheating on him or thinking of cheating on him. He had acted the same way two years ago, when he was thinking of cheating on her.

“Not next week

but the week after,” Ted said.

Heather carried the plates into the kitchen. “For how long?”

“Couple days.” Ted sat back in his chair and considered getting up to help, but he felt too comfortable and instead watched Heather move around the kitchen.

“I think I’ll stay. I could use the time,” she said, scraping off the dishes. “Don’t let Leslie eat a lot of junk. She’s gaining weight again. I’m going to have to put her back on that diet.”

Ted didn’t argue with the diets; he let Heather do as she wished. She was convinced Leslie’s “episodes” were the result of poor nutrition. Ever since the social worker had paid them a visit, Heather had been taking out stacks of books from the library: Superfoods for Special Kids, Brain Foods for Teens, Healthy Diets for Super Kids. Ted thought these so-called “episodes” — the screaming and the violence — were nothing more than the antics of a spoiled brat. Leslie was immature, afraid to grow up; she still played with Barbie dolls at fourteen. It was ridiculous, Leslie calling child services for a slap across the face, making them sit through a family assessment, the counsellor’s critical gaze, the long pauses as he cautiously chose his words. Ted would never forget the look of distress and satisfaction on Leslie’s face when he opened the door to the man with the guarded smile and the file folder. Her expression read as both a question and an affirmation: I can do this to you.

Heather hadn’t been the same since, hadn’t been the same with him since. It was an embarrassment, two professionals being interrogated like that. It was as though she blamed it on him, somehow — his late nights and extended workweeks — but he wasn’t the one who had raised his hand and he wasn’t the one who had called child services.

Ted got out of his chair and went over to Heather, who stood at the sink rinsing the dishes. “Maybe the trip will cheer Anna up,” Heather said. “She’s been miserable to me.”

He leaned into her, bent to her ear. “Anna’s fine. She’s always fine,” he whispered. “She’s the good one, remember?” Anna was the child who sang you songs while she helped load the dishwasher, who left her dirty boots at the door, who cleaned her plate without bribery. Leslie was the child who ate glue.

“I don’t know if I’d go that far,” Heather said, shaking her head. “I think she might be flunking out of Camosun.”

“Anna got straight A’s in high school. She’s adjusting.” He wrapped his arms around her and laced his fingers near her stomach. “The trip will be good for both of them. I’ll talk to them, straighten things out. We’ll eat vegetables all weekend.” He kissed the back of her neck. “I’m trying to make you happy.” Heather gently unlaced his fingers and lifted his arms off her, continuing to rinse the dishes. Her lips pressed together in a tight smile. “What’s the joke?” Ted asked.

She shook her head. “Nothing. Take the girls. You’ll have fun.”

THEY’VE ONLY BEEN DRIVING along the winding island road for ten minutes when Anna starts to groan in the back seat. “Pull over. I’m going to be sick.”

“Carsickness is all in your head,” Leslie says.

“Shut up. Dad, stop.”

As soon as Ted pulls over Anna throws open the door, stumbling along the side of the road, clinging to the long grasses beside the ditch. Leslie hops out of the car and scans the bushes, looking for the best blackberries and popping them in her mouth. Ted flips open his phone — the screen shows emergency service only. His client will have to wait.

Mist hangs back in the forest like a curtain, creating a sound barrier, leaving everything dewy and still and filling Ted with an unjustifiable sense of hope — for what, he has no idea. Maybe the property, the potential summer house. This part of the island is sheltered from the winds off the strait, the branches of the towering evergreens fossilized in their stillness, not a quiver in their needles. Something in the air — the smell of fir — is stirring good memories, and when the inevitability of his own death suddenly grips him, Ted reassures himself, knowing that when that day comes, he’ll be able to look back on this trip with a sense of accomplishment: he’ll buy the property, hand down a parcel of land to his girls. It’s as though he has woken clear-headed from a bad sleep. He hasn’t felt this way since Anna and Leslie were young, when Ted and Heather would take them island-hopping in the summer, spending a week ferrying around the Gulf Islands. The girls loved the ferries; they would stand out on deck at the bow, mouths wide open in the salty wind. Anna could name all the islands they passed — Pender, Saturna, Mayne. One summer, for no special reason — either he or Heather was busy with work — they stopped going, and they haven’t been back since.

Leslie opens her stained hand and offers Ted a selection of plump blackberries. He thanks her and pops one in his mouth, savouring its tartness. She eats the rest of the handful, dark purple juice oozing out from between her lips. Ted laughs and puts his arm around her, pulling her toward him and giving her shoulder a squeeze. “We haven’t done this in a while, have we?” he says.

“It reminds me of something.” Leslie wipes the juice off her lips with the back of her hand and cranes her neck to take in the tops of the trees. “Did we come here when we were kids, like, on this exact road?”

“Not here,” Ted says. “This is all new.”

Anna walks back toward them, pale and unsteady.

“Did you puke?” Leslie asks, getting back in the car.

Anna follows her, getting in the front seat. “Keep going, but don’t take the turns so fast.”

“A deer!” Leslie says, pointing to a doe nipping at the underbrush along the edge of the forest.

“I’m sure we’ll see lots of them,” Ted says. “They don’t have many predators here.”

“Am I supposed to keep my eyes open or closed?” Anna asks, her eyes squeezed shut.

“It’s so cute. Come on, Anna, look,” Leslie says, shaking her arm.

“Fuck off,” Anna shouts, shoving her sister to one side of the car. The sharpness in her tone shocks them all into silence for a few seconds. Ted turns on the engine and the deer runs into the forest, vanishing behind the wall of fog.

“Why are you so pissy?” Leslie says, her voice quiet and hurt.

“Leslie, don’t say pissy,” Ted says, turning back to the road.

“Anna can say ‘fuck off’, but I can’t say ‘pissy.’”

“The cabin’s on the edge of that hill.” Ted points up ahead.

“Where’s the ocean?” Leslie asks.

“The cabin’s not on the ocean. It’s on a lake.”

“Oh.” Leslie sounds disappointed. Anna lurches forward in her seat with her hand over her mouth. “Stop the car.”

THEY EAT AN EARLY dinner of cold cuts, bread, and sliced tomatoes with salt and pepper. The girls become quiet and sullen in their new environment. Leslie’s giddiness disappears. They’re both disappointed the cabin has no television. Ted made a production of the bicycles propped up against the garage awning, taking one for a quick circle of the front yard as the girls stood, arms crossed, unimpressed.

Ted and Anna drink wine out of mugs because they can’t find glasses, and Ted gives Leslie two small tasters. This perks her up right away and after the first sip the chatter starts once again. She hoots like an owl, saying, “Listen. It’s weird. It’s so quiet. Hoo, Hoo.” Over dinner their conversation is self-conscious, but loosens up as Ted pours a second glass of wine for Anna and himself. When he mentions Leslie’s “boyfriend on the ferry,” she blushes and Anna teases her ruthlessly. On the bookshelf Leslie finds a deck of cards and hands it to Ted. “What do you want to play?” he asks as he shuffles them, enjoying the sound of the deck breaking.

“Go Fish,” Leslie says. She reaches for the wine bottle and Ted stops her, placing his hand over hers. “I don’t think so,” he says.

“Come on. You barely gave me any.”

Ted looks to Anna who shrugs and lo

oks around as if to say, Is there any harm, here in the middle of nowhere? “A drop,” Ted says, pouring a finger of wine into her mug. “Don’t tell your mother.”

Leslie grins, pleased. Her teeth are red.

THEY PLAY CARDS ON the porch for the better part of an hour, shouts of Go Fish echoing across the lake, before Ted leaves the cabin, driving back to the ferry dock in search of cell reception and a pie for dessert. He buys blueberry at the market and tries his client first, getting voicemail, and then calls Heather. Her tired voice makes him instantly sleepy. “How are the girls?”

“Good. In fact, they’re great. Leslie’s at least trying to behave.”

Heather laughs softly on the other end of the line and for a little too long; Ted starts to think the joke may have been about something else. “It’s quiet here without them,” she finally says.

“It’s quiet here too.” When he says these words, Ted’s eyes go instinctively out to the ocean, where the last ferry of the day is loading. He suddenly feels paranoid, as though at this very moment, Heather may have a naked man in bed beside her. “You’ll have to come with us next time.”

“Can I talk to them?” she says, ignoring his offer.

“They’re at the cabin. There’s no phone, no cell service, no TV. It’s rustic. I came into town to buy pie.”

“What about Leslie’s diet?”

“We’re just having some fun.”

Silence fills the phone line. The ferry leaves the dock and sends a puff of smoke into the air.

“I should go,” Ted says, suddenly feeling restless and annoyed.

“I should too.”

Neither one of them says goodbye.

TED CAN SEE THE cabin from a fair distance along the road. The lights in all the rooms are blazing, the cabin’s reflection flickering on the surface of the black lake. He has an urge to abandon the car and walk the rest of the way, take in the night sky and the smell of the firs. His buzz is wearing off and his true urge is for a walk with a half-drunk bottle of wine. He drives the rest of the way to the cabin, and as he steps out of the car, he can hear the girls laughing the way they used to when they were small, their fast-paced babble like hummingbird wings, out of place in the dark evening. He stands in the driveway for a few minutes trying to catch bits of their conversation, but most of what they’re saying is nonsensical.

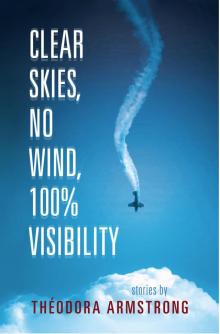

Clear Skies, No Wind, 100% Visibility

Clear Skies, No Wind, 100% Visibility