- Home

- Theodora Armstrong

Clear Skies, No Wind, 100% Visibility Page 10

Clear Skies, No Wind, 100% Visibility Read online

Page 10

“Coulis,” Charlie snaps at James, watching him plate a raspberry chocolate mousse. He’s forgotten the dot of mango sauce that cheers the presentation. Charlie slices green onions, the blade blurring under his fingertips.

“Watch your — ” James stops himself before he can finish his sentence. He’s watching Charlie’s knife with apprehension.

“Are you telling me how to cut onions?” Charlie snaps, laying his knife down on the cutting board.

“No, Chef,” James says, bowing his head. Charlie goes back to his slicing and looks up to see Susan smiling at him. “Almost forgot,” she says. “Let’s take a seat at table thirty-nine.” Salary negotiations are always conducted in public places where witnesses are present.

Their table is near the back of the restaurant, away from the smattering of customers and out of staff earshot. Susan sits across from Charlie, pausing to carefully shuffle in all the corners of her papers before looking up and shining a beatific smile at him. It sends a sharp stab through Charlie’s liver. “First and foremost, Charlie, the Logan Group wants me to tell you they appreciate everything you’ve done for this restaurant.” Charlie sits back with a nod, folding his arms across his chest, ready to accept the short soliloquy of praise with a firm and dignified handshake. He’ll even forget the comment about fucking up the barnacle. Susan talks for several minutes, extolling his virtues, pointing out instances where he was vital to the restaurant’s success, before laying her hands flat on the table, palms up, and bowing her head in concession. “But at this point the Logan Group cannot increase your remuneration.”

Charlie sits stunned for a moment, staring at the bright pink lipstick Susan’s slathered on to distract from her eye. He leans forward and turns her papers toward him. “Are you reading that from a script? Speak English, Susan.”

“I think you know what I’m saying.” She holds his gaze. He can see a hint of pleasure in her good eye. Blood runs hot up his neck and boils in his cheeks. He wonders if all the whiskey he’s consumed this afternoon has made him more flammable. “Don’t bullshit me, Susan. I’ve been waiting a long time for this.”

“Charlie,” she says, yanking her papers back and covering them with her arm. “Don’t shoot the messenger.”

“What the fuck, Susan? I’m going to be a father.”

“Oh God, Charlie,” Susan says, rubbing her forehead and looking around the restaurant to see if anyone’s heard him. “I’m getting a migraine.”

“A migraine?” Charlie says, raising his voice. “Right, because this is about you right now.”

“Listen,” she says, gesturing to the mostly empty dining room, “You know what they are like.” When she says they she means millionaires. People assumed that wealthy clientele made for booming business, but in fact there was a reason they were rich: the servers pried each and every loonie from their tightly clenched fists. “We’re a few bad months away from sticking someone on the street corner in a salmon suit with a sign advertising half-priced lunch entrees.”

“I know how much you make. I’ve seen your paystubs.”

“Food costs, Charlie?” A little vein is beginning to bulge in Susan’s forehead. “Duck? Seven days of duck? If it weren’t for my Wine and Jazz Wednesdays we wouldn’t even be covering costs.”

“Right, or maybe it was those flowers you planted.” Last week she was out front in her suit jacket and miniskirt, bent over the wine barrel planters with a trowel. The week prior she strung twinkly lights around the entrance that blinked at seizure-inducing speeds. “No, Susan, it’s the goddamn food. People come to a restaurant to eat.”

“Maybe if you started paying for all the booze you drink here.” Her voice has turned nasty. “You’re drunk right now, for Christ’s sake.”

“Why did you let me walk around all afternoon like an asshole?” he says, ignoring her comment. His fists are clenched under the table and even with concentration he can’t seem to loosen them. He’s suddenly aware of the nothingness they’re strangling in their grip. Open or closed, they’re still empty.

“This isn’t French fine dining, Charlie. It’s not Le Carré.” His fists release, lay limp in his lap. It takes him a second to regain control of his limbs. He’s never mentioned his father’s restaurant to Susan.

“Well, this went well,” she says, shuffling her papers together and standing up. “Six months and we’ll take another look.”

He stands quickly with a grunt. He doesn’t appreciate her getting up first, leaving him alone at the table staring up at her; she should have given him some kind of warning so they could stand together. He watches her walk across the dining room, straightening wine glasses as she goes along. James and Rich are trying desperately not to look at him. Six months will drag like a ship anchor weighed down by five hundred pairs of crab cakes eaten by the same five old biddies on rotation.

“Incompetent,” Charlie mutters back in the kitchen, pushing Rich out of the way. “I’ll do this one,” he says, ripping the chit and rubbing salt and pepper into a bright red hunk of meat. He pushes his cup at Rose as she walks by, “I need another.” The anger begins to sizzle all over his skin, his vision blurring. He throws the steak on the grill and sees his father standing by the prep counter, twirling in a maddened rage, throwing handfuls of limp spaghettini at the wall. No, this is not Le Carré — that message was clearly delivered by a birthday card peacock this morning. Rose pushes a drink at him. None of them understands how lucky they are to have him sweating in this restaurant. Their pockets would be fat with moths instead of bills if it weren’t for him. He brushes the steak with generous layers of butter and watches the juices drawn out of the flesh spit as they drop into the fire. “Are you watching, Rich?” Charlie turns the steak once and admires its grill marks. “You don’t turn it and turn it,” he says to James, motioning to the meat. “Don’t say you don’t do that, because I’ve seen you. Goddammit. Too slow.” He grabs the bowl of potatoes from James and whips them himself, creating thick white peaks. “Creative license,” he shouts at Rich, pulling several spices down from the rack and sprinkling them liberally. He brings his nose down to plate level, flourishing the garnish before setting it delicately over the whipped potatoes and drizzling the leftover juice from the steak over the vegetables. “Let go, just let go” Charlie says, slapping measuring spoons out of James’ hand. They go clattering across the kitchen tiles. “There,” Charlie says, plating the steak and kissing the tips of his fingers. “Parfait!” He throws the plate onto the pass-bar. “Runner!”

There are only a few tables of customers left. Two West Vancouver cougars on their second bottle of rosé laugh together — probably about their husbands’ shortcomings, Charlie guesses. A young couple shares dessert at the other end of the restaurant, the guy texting on his phone as the girl concentrates on gathering up every last remaining drop of chocolate raspberry coulis on the plate. The well-heeled salt-and-pepper boomer and his portly wife taste wine while Rose stands dutifully by their table, presenting the bottle.

Charlie carries his drink to the back stairs for a cigarette. A carved pumpkin from last week’s Halloween decorations has been left out here to rot, its sad, sunken face glaring at him. He glares back. It grimaces. He grimaces. It mocks him and he picks up the fool thing, its softened features sinking further into themselves, and bunts it down the flight of concrete stairs, watching it come apart with soft, wet squelches, a ring of pumpkin stuck around his shoe. He knocks back his drink and bends over to scrape off the pumpkin guts, almost tipping over — he’s drunker than he thought. The rain suddenly comes down harder, stinging his head, and he steadies himself against the railing before heading back into the restaurant. “Cleanup on aisle four.”

“Huh?” The waterlogged dish boy looks stunned that Charlie is actually speaking to him.

“Clean up the back stairs before someone cracks their skull,” Charlie says, slurping his drink. The boy drops his rag a

nd slinks out the back hall.

“Charlie?” Susan’s head pops around the corner. “It’s Aisha again.”

“No time. Tell her to call after the dinner rush.”

Heavy metal music thumps from the small stereo next to the dishwasher. Charlie yanks the cord out of the wall and carries the stereo to the back steps, launching it into the dumpster next to the dish boy, who is picking bits of obliterated pumpkin up off the concrete. The stereo lands with a soft thud on a pile of mouldy hamburger buns and vegetable peelings. Dish Boy stares wide-eyed for only a moment and then pretends not to notice his stereo in the garbage as he walks back up the steps into the restaurant. Charlie is impressed with the boy’s recovery. He pulls out another cigarette and smokes it in the doorway, watching the rain shoot down from the sky. When he comes back inside, Dish Boy is quietly staring at the dishwater.

“Like this,” Charlie says, pushing him aside and furiously scrubbing at the pans collecting in a teetering pile on the counter, sending dishwater on the floor. “Do it like this.” He heaps scrubbed bowls and ladles and cutting boards with a clang and then shoves them so they go skidding along the soapy surface of the metal counter and come crashing onto the floor. “Like that,” he says, chucking the dishrag into the sink.

Charlie stalks back into the kitchen and dices an onion so he can feel the sting in his eyes. Rose pushes a plate with the steak half-eaten back across the pass-bar. “Overdone,” she says. “Inedible, supposedly,” she shrugs. “Not my words.”

“Bullshit.” Charlie pokes the hunk of meat and holds it up to the light, turning it this way and that, before throwing it back on the plate. “You tell him that steak is cooked exactly the way he ordered it.”

“Okay.” She shrugs again, taking a detour into the office with the plate before heading back to the table. Susan comes out of the office and surveys the dining room. Before Rose even reaches the table, the well-heeled boomer wags his finger as though he is scolding a small child.

“He wants to talk to you,” Rose says, dropping the plate on the pass-bar with a clatter.

“Charlie,” Susan warns, as he strides past her with the plate, the steak sliding around dangerously, nearly becoming airborne several times. Martin has detected the tension mounting in the dining room, his eyes darting from the dissatisfied table to Charlie to Susan while he picks at the scab above his lip.

“Good evening, sir,” Charlie says, flourishing the plate before lowering it to float right under the boomer’s nose. Rose runs a wet rag over the tabletops while Martin jerks around the room throwing down fresh cutlery on the empty place settings, both of them attempting to get close to the action in anticipation of the drama about to unfold. “Perhaps in this dim light it’s difficult to see, but I can assure you your steak is cooked to your specifications.”

“I already told the waitress I won’t be paying for it.” When the boomer speaks he does so without looking at Charlie and gazes at his wife instead, a calm, satisfied smile on his face. “And honestly, my wife’s meal isn’t very good either.”

“We simply won’t come back,” the wife says, limply dangling her fork over the food. The man seems relaxed, as though he weren’t that hungry to begin with. Charlie studies his profile for a minute and recognizes him instantly as his Chef de Partie from Le Remoulade, a slightly older, more distinguished looking version. When Charlie first started there as a Third Cook, the man took him under his wing, helped him advance all the way to First Cook.

“Do you know who I am?” Charlie says looking into the man’s face.

“Should I?” The man smirks, misunderstanding, ready for a game. The wife crumples her napkin and places it definitively on top of her seafood risotto. “We won’t come back,” she says again.

Charlie stares at the man, giving him a chance to let his features register, but the man shrugs, bored of the game already. “I give up. Who are you?”

A snort escapes Charlie’s nose as he drops the plate on the table. “No one.” He turns to head back to the kitchen, but his legs fail to communicate with his torso. “I’m a ghost.” His last words are lost in the clatter as he falls over one of the empty tables. Suddenly Rose is under one of his arms and Susan the other. A shattered wine glass twinkles in the carpet. “Okay, Charlie.” He can’t tell who the words come from, but they are gentle.

“Thank you,” he says, shaking the women off of him. The gratitude is tinged with both sincerity and reproach. “Give your steak to your dog for all I care,” he shouts over his shoulder at the man and his wife. Charlie walks to the bar and motions to the glorious bottles of liquor behind Martin.

“Why don’t you take a breather,” Martin says, stacking pint glasses.

“I’m not looking for anything,” Charlie says. He’ll make his own drink, he just needs Martin out of the bar. “Get those people a doggie bag.”

But instead of walking behind the bar something draws him away toward the windows. In the reflection of the glass he can see Susan and Rose placating the wife, her bangs floating up from her forehead with each angry puff. Her husband is already out the door. Anyone left in the restaurant is making a hasty exit now, pulling wallets out of their pockets, sliding visas in billfolds. The storm has taken on a new dimension, one Charlie has never seen before. Below he watches the boomer lean into the gusts of wind as his wife scurries to catch up to him. The ocean looks as though it is reaching out, trying to take the restaurant into its insatiable belly. He stands close enough to the window to feel a chill over his face. The wind is buffeting the glass, trying to find any crack where it can sneak in. The pane rattles a few millimetres from his nose. “Charlie.” Susan’s voice floats somewhere behind him. “Phone for you.” He doesn’t move. The rattling is a distraction. He snaps out of his daze and saunters over to the phone, swaying slightly. When he picks up the receiver, he expects to hear his father on the other line: “Ça va, mon petit fantôme?”

AS SOON AS HE opens the back door of the restaurant, Charlie hears the ocean. The wind whips around his head and he pulls his toque low over his ears, making a dash for his car. The Douglas spruce towering overhead dips unnaturally, creaking and groaning as though it might come crashing down on his head. He watches it cautiously for a moment before climbing into the front seat. Down the way, one of the binners that frequent the alley behind the restaurant weaves between the garbage cans and falls on his knees in a large puddle, his hair a tornado above his head. The evergreen branches scrape across the roof of the car. “Shit,” Charlie says, putting the car in gear and peeling out of the spot. He slows down as he approaches the homeless man, worried he’ll roll into the middle of the road or leap in front of the car. As he passes, the man looks up at Charlie, and it’s Topher on his knees, his eyes dark and menacing with booze. Charlie only considers stopping for a moment.

As he drives down the empty streets strewn with tree detritus, Charlie can see the waves pounding the shore. The road swims in front of his eyes. How much did he have to drink tonight? More than usual — seven, eight, maybe nine drinks? Could’ve been more, he wasn’t exactly counting. Less than Topher, for sure. Baby’s early, Charlie. It had been Aisha’s sister on the line, her disembodied voice cutting through the telephone.

Charlie can see the generators exploding in the distance, bursts of cartoon-radiation green. The lights are out around the bridge and in the city, a gaping void where there should be the glittering of illuminated towers. The causeway through Stanley Park is covered with a blanket of broken branches, the trees swaying like pendulums. Charlie comes around a bend and slams on the brakes, the car skidding perpendicular to the road. A massive pine is down, blocking the entire causeway.

Rain pelts the car, a constant barrage sliding down the windshield. Charlie pulls off his toque and blinks at the tree, rubbing his head as if trying to conjure an intelligent thought. He searches his pockets for his phone before seeing it in his mind’s eye, sitting on the

prep counter next to the cutting board. He forgot it in his rush to get out the door. Out of the car, the rain pours over him like a cold shower. The street is deserted. Fear nestles deep into his belly, lifting the haze of alcohol he’s been swimming through the entire evening. In the distance, Charlie can hear the sound of sirens, the sound of waves crashing, the sound of someone yelling at him, You’re awake, Charlie. You are wide awake. It’s not like a light bulb illuminating his brain, it’s the kind of frickin’ bolt of white-hot lighting that brings Frankenstein’s monster to life. Charlie scrambles over the tree and starts to run.

~

THE CBC IS REPORTING that a red cedar estimated to be over a thousand years old was felled by last night’s winds. The largest of its kind in the world, the reporter says, now lying prostrate on the forest floor. Charlie can’t imagine something of that size, something that had survived hundreds and hundreds of years, uprooted and toppled in the dead of night. The tree must have made a terrible noise as it came down, shuddering and groaning with Godzillian force, a mythic reptile slain.

The ocean is dead calm now, cool, steely, shimmering in the early morning light, circling the tall, shut-eyed buildings of the city like a sheltered lake, without a hint of the rage from the night before. Charlie stands in the middle of the empty restaurant looking out across the mouth of Burrard Inlet at what is left of Stanley Park. The entire west side has been ravaged by last night’s storm. When he drove through the causeway on his way to work this morning, the forest was noticeably thinner, ocean appearing where trees once grew tall and dense. He sips his scalding coffee and surveys the altered landscape. He has a headache from his hangover, but it feels far away, like an afterthought. The fire hasn’t been started in the oven and the restaurant is cold. He can see his breath. Martin is sleeping on the leather couch in the lounge, snoring lightly, one of the patio blankets pulled up under his chin. Charlie lets him sleep and walks out back to collect the firewood. The winds have piled garbage into one corner of the parking lot and seagulls are pecking away happily at a loose scattering of soggy french fries. He piles a few logs into his arms and trudges back up the steps to start the fire.

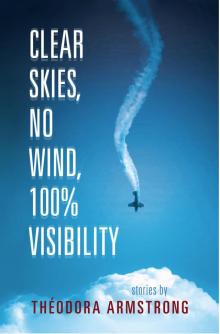

Clear Skies, No Wind, 100% Visibility

Clear Skies, No Wind, 100% Visibility